UNIT 2 |

OBJECTIVES

REFERENCES

1. Upadhyay, Vaibhav, and Yang-Xin Fu. “Lymphotoxin signalling in immune homeostasis and the control of microorganisms.” Nature reviews. Immunology vol. 13,4 (2013): 270-9. doi:10.1038/nri3406

2. Eberl G. A new vision of immunity: homeostasis of the superorganism. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 [PubMed]

3. Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

4. Robynne Chutkan. The Microbiome Solution.

- Discuss the role of Lymphotoxins in Obesity

- Describe the location and function of Gut Associated Lymphoid tissue

- Discuss the Hygiene and modern Plague Hypothesis

- Review the mechanism of microbiome disruption secondary to food intake

REFERENCES

1. Upadhyay, Vaibhav, and Yang-Xin Fu. “Lymphotoxin signalling in immune homeostasis and the control of microorganisms.” Nature reviews. Immunology vol. 13,4 (2013): 270-9. doi:10.1038/nri3406

2. Eberl G. A new vision of immunity: homeostasis of the superorganism. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 [PubMed]

3. Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

4. Robynne Chutkan. The Microbiome Solution.

Lymphotoxin

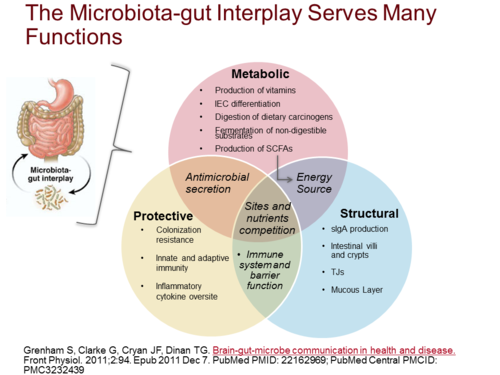

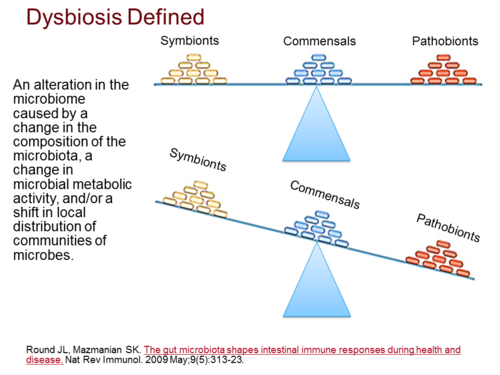

Lymphotoxin (LT) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily that was originally thought to be functionally redundant to TNF, but these proteins were later found to have independent roles in driving lymphoid organogenesis. More recently, Lymphotoxins has been shown to actively contribute to our immune responses. Lymphotoxis regulates dendritic cell and CD4+ T cell balance (homeostasis) in the steady state and determines the functions of these cells in times of infection or pathogenic challenges. The Lymphotoxins are essential for controlling pathogens and even contributes to the regulation of the intestinal microbiome, with recent data suggesting that Lymphotoxins induced changes in the microbiome promote METABOLIC DISEASE. A newly defined roles for Lymphotoxins with a particular focus on how it regulates innate and adaptive immune responses to microorganisms were also established.

Mucosal immunity lies in a delicate balance with the microbiome; a consequence of this symbiosis is a reciprocal relationship between host and microbe that contribute to host health. A consequence of the work on the “obesity-associated microbiome” is that environmental exposure, either in the form of high fat diet or through colonization of obesity-inducing microbiome may actually play a critical role in the pathogenesis of obesity and associated diseases. The microbiome lie in a delicate homeostasis with host immunity, and given the epidemiological data linking lymphotoxin to obesity and the key role of lymphotoxin in regulating mucosal defense.

Gus Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT)

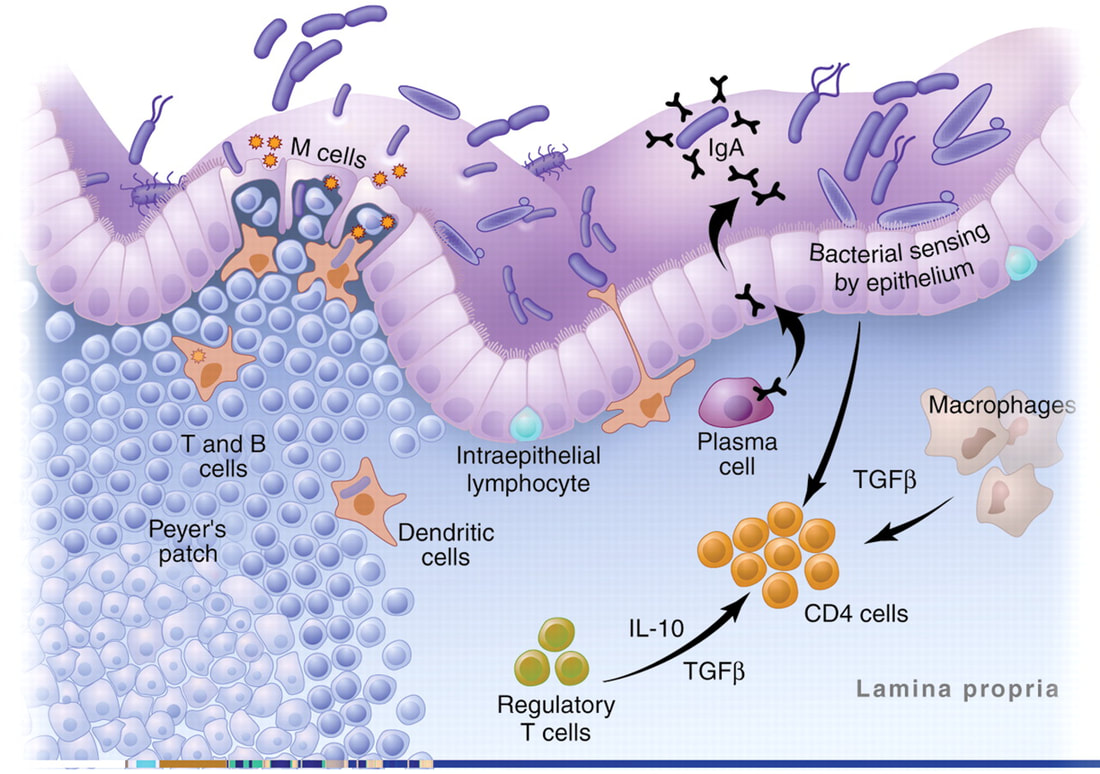

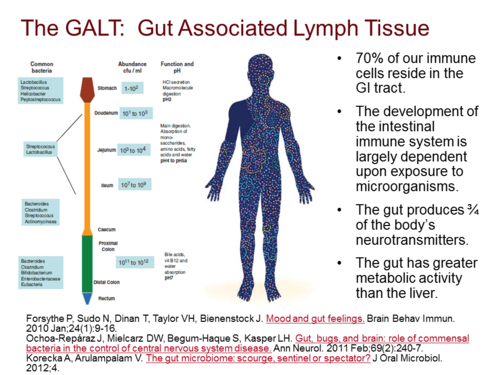

The intestinal mucosa is the major site of contact with antigens (a toxin or other foreign substance which induces an immune response in the body, especially the production of antibodies), and it houses the largest lymphoid tissue in the body. In physiological conditions, microbiome and dietary antigens are the natural sources of stimulation for the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) and for the immune system as a whole.

Germ-free models have provided some insights on the immunological role of gut antigens. However, most of the GALT is not located in the large intestine, where gut microbiome is prominent. It is concentrated in the small intestine where protein absorption takes place. In here the involvement of food components in the development and the function of the immune system was established. Studies have already shown that dietary proteins are critical elements for the developmental shift of the immature neonatal immune profile into a fully developed immune system. The immunological effects of other food components (such as vitamins and lipids) were also found. Most of the cells in the GALT are activated and local pro-inflammatory mediators are abundant. Regulatory elements are known to provide a delicate yet robust balance that maintains gut homeostasis.

The intestine is the largest interface between the body and the external environment. Most contacts with foreign antigenic materials occur at the gut mucosa. It has been reported that 130–190 g of protein is absorbed in the small intestine daily and the gastrointestinal tract harbors approximately 1014 microorganisms of more than 1000 species. Moreover, it is also known that the intestine houses the most abundant lymphoid tissue in the body. There are 1012 lymphoid cells per meter of human small intestine. The number of immunoglobulin (Ig)-secreting cells located in the gut exceeds by several fold the number found in other lymphoid organs altogether. Lymphocytes that compose the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) are either part of lymph-node-like structures such as Peyer’s patches (PP) or scattered throughout the lamina propria and intraepithelial spaces of the intestine in such a way that it is impossible to dissociate functionally epithelia and lymphoid components.

Germ-free models have provided some insights on the immunological role of gut antigens. However, most of the GALT is not located in the large intestine, where gut microbiome is prominent. It is concentrated in the small intestine where protein absorption takes place. In here the involvement of food components in the development and the function of the immune system was established. Studies have already shown that dietary proteins are critical elements for the developmental shift of the immature neonatal immune profile into a fully developed immune system. The immunological effects of other food components (such as vitamins and lipids) were also found. Most of the cells in the GALT are activated and local pro-inflammatory mediators are abundant. Regulatory elements are known to provide a delicate yet robust balance that maintains gut homeostasis.

The intestine is the largest interface between the body and the external environment. Most contacts with foreign antigenic materials occur at the gut mucosa. It has been reported that 130–190 g of protein is absorbed in the small intestine daily and the gastrointestinal tract harbors approximately 1014 microorganisms of more than 1000 species. Moreover, it is also known that the intestine houses the most abundant lymphoid tissue in the body. There are 1012 lymphoid cells per meter of human small intestine. The number of immunoglobulin (Ig)-secreting cells located in the gut exceeds by several fold the number found in other lymphoid organs altogether. Lymphocytes that compose the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) are either part of lymph-node-like structures such as Peyer’s patches (PP) or scattered throughout the lamina propria and intraepithelial spaces of the intestine in such a way that it is impossible to dissociate functionally epithelia and lymphoid components.

There is a direct influence of dietary components in the physiological operation of the immune system, in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, as well as in the development of adverse reactions to food proteins. Feeding is the major and most frequent occasion in which the organism contacts foreign proteins and other immunologically relevant molecules. Nutrients have biological and immunological importance in all stages of life. They are essential materials for the survival of organisms having a great impact in the body’s physiology from their absorption, metabolism until their excretion. A collection of recent findings on antigen presentation as well as on the signaling pathways triggered by amino acids, lipids, and vitamins confirm the critical role of dietary components and nutrition in the basic function of the immune system.

The first contact of the immune system with nutrients occurs in embryogenesis. Nutrients from the maternal circulation are the structural basis for the development of new body tissues. The diversity, quality, and quantity of these nutrients modulate the functional characteristics of body tissues. After birth, breastfeeding also provides immune cells, immunoglobulins, and important cytokines that are key players in the immunological setting of the newborn. These reports clearly point to the role of an appropriate supply of dietary proteins in the formation and maintenance of lymphoid structures such as the gut mucosa.

There is strong evidence that nutrients are required for the early establishment and maintenance of gut function, even when there is not a context of malnutrition. Presence of intact proteins in the diet has a critical role in the development and maturation of the immune system. here are many other components in diet, beyond macronutrients, that affect the activity of immune cells. It has been extensively shown that anti-oxidant vitamins and trace elements (vitamins C, E, selenium, copper, and zinc) counteract potential damage caused by reactive oxygen species to cellular tissues, modulate immune cell function through regulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, and affect production of cytokines and prostaglandins.

Vitamins are essential nutrients needed in low amounts for the normal functioning of the body. Many have direct effects in the immune system. Vitamin E and C are anti-oxidants but also prevent the development of aortic lesions by inhibiting the expression of adhesion molecules and by modulating macrophage and monocyte function. Some immune cells are capable of metabolizing vitamin D to its active form 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), and that is why this vitamin is easily found in lymphoid sites at high concentrations.

Vitamin A is also known as retinol. Apart from its immunomodulatory ability, retinol has a significant anti-oxidant property and it is imperative to the good functioning of the visual system, for growth and development of the whole body, for the maintenance of epithelial cell integrity and for reproduction. Although vitamin A is easily found in many types of food, its deficiency is a world health problem, and the ecommended daily consumption for this nutrient is 900–700 micrograms, depending on gender for adults, 770 micrograms for pregnant and 1300 micrograms for lactating women. Usually vitamin A is ingested as retinol, or in its pro-form, as carotenoid. The most active metabolite of this compound is retinoic acid (RA), which binds to specific nuclear receptors in many cell types.

There is strong evidence that nutrients are required for the early establishment and maintenance of gut function, even when there is not a context of malnutrition. Presence of intact proteins in the diet has a critical role in the development and maturation of the immune system. here are many other components in diet, beyond macronutrients, that affect the activity of immune cells. It has been extensively shown that anti-oxidant vitamins and trace elements (vitamins C, E, selenium, copper, and zinc) counteract potential damage caused by reactive oxygen species to cellular tissues, modulate immune cell function through regulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, and affect production of cytokines and prostaglandins.

Vitamins are essential nutrients needed in low amounts for the normal functioning of the body. Many have direct effects in the immune system. Vitamin E and C are anti-oxidants but also prevent the development of aortic lesions by inhibiting the expression of adhesion molecules and by modulating macrophage and monocyte function. Some immune cells are capable of metabolizing vitamin D to its active form 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), and that is why this vitamin is easily found in lymphoid sites at high concentrations.

Vitamin A is also known as retinol. Apart from its immunomodulatory ability, retinol has a significant anti-oxidant property and it is imperative to the good functioning of the visual system, for growth and development of the whole body, for the maintenance of epithelial cell integrity and for reproduction. Although vitamin A is easily found in many types of food, its deficiency is a world health problem, and the ecommended daily consumption for this nutrient is 900–700 micrograms, depending on gender for adults, 770 micrograms for pregnant and 1300 micrograms for lactating women. Usually vitamin A is ingested as retinol, or in its pro-form, as carotenoid. The most active metabolite of this compound is retinoic acid (RA), which binds to specific nuclear receptors in many cell types.

Hygiene and Modern Plague Hypothesis

Many of us were brought up to believe that it's better to be clean than dirty. But evidence is mounting to show that if you start from that premise, you will arrive at the wrong destination as far as human health is concerned. The microbial communities established in our bodies at birth, during infancy, and in early childhood mold our health as we grow and help determine whether or not we develop illness. The unwilding of our internal landscape has created health challenges we never anticipated and led to the emergence of a new breed of disease.

MICROBES AND MODERN PLAGUES

In 1932, gastroenterologist Burrill Crohn, MD, and his colleagues at Mount Sinai Hospital published a paper describing fourteen patients who had a peculiar findings in the small intestine at surgery that were unlike anything that had previously been seen. The abnormalities were in the end of the small intestine - an area known as the ilium - so they called the new disease terminal ileitis, although it would eventually come to be known as Crohn's disease.

In 1932, gastroenterologist Burrill Crohn, MD, and his colleagues at Mount Sinai Hospital published a paper describing fourteen patients who had a peculiar findings in the small intestine at surgery that were unlike anything that had previously been seen. The abnormalities were in the end of the small intestine - an area known as the ilium - so they called the new disease terminal ileitis, although it would eventually come to be known as Crohn's disease.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn's disease and its sister condition, ulcerative colitis, are examples of autoimmune diseases. They represent a new breed or malady, sometimes referred to as modern plagues, which has emerged in the last century and includes conditions such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis, type 1 diabetes, lupus, multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis, and eczema. Their hallmark, regardless of what organ they affect, is that the immune system wages war against the body's own healthy tissues, leading to chronic inflammation.

There are almost a hundred different types of autoimmune diseases. Chances are you or someone in your family suffers from one, since they affect about fifty million people in the United States alone. Different autoimmune diseases frequently affect the same person, suggesting a common cause with varied manifestations rather than multiple distinct ailments. The million-dollar question is whether that common cause is an abnormal immune system overreacting to normal stimuli in the environment, or a normal immune system responding to an abnormal trigger.

There are almost a hundred different types of autoimmune diseases. Chances are you or someone in your family suffers from one, since they affect about fifty million people in the United States alone. Different autoimmune diseases frequently affect the same person, suggesting a common cause with varied manifestations rather than multiple distinct ailments. The million-dollar question is whether that common cause is an abnormal immune system overreacting to normal stimuli in the environment, or a normal immune system responding to an abnormal trigger.

Understanding the relationship between our immune system, our microbial environment, and our genes is critical to figuring out why people suffer from these diseases and how to heal them. Since most of our germs and more than half of our immune system are located in our gut, taking a closer look at Crohn's disease in the context of the microbiome may yield some valuable answers.

Guts, Germs, and Genes

Dr. Crohn was convinced that this new disease, which caused inflammation, weight loss, and diarrhea, was the result of a bacterial infection, although not everyone shared his view. At that time, Crohn's disease was most often diagnosed in people of Jewish heritage, and the prevailing Wisdom was that Crohn's was a genetic rather than an infectious disease. The bacterium in question was Mycobacterum avum subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). It was known to infect the same area of the ileum in cows and other ruminants, causing a Crohn's-like wasting diarrheal illness in these animals called Johne's disease (after the German veterinarian who described it in 1905).

Dr. Crohn was convinced that this new disease, which caused inflammation, weight loss, and diarrhea, was the result of a bacterial infection, although not everyone shared his view. At that time, Crohn's disease was most often diagnosed in people of Jewish heritage, and the prevailing Wisdom was that Crohn's was a genetic rather than an infectious disease. The bacterium in question was Mycobacterum avum subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). It was known to infect the same area of the ileum in cows and other ruminants, causing a Crohn's-like wasting diarrheal illness in these animals called Johne's disease (after the German veterinarian who described it in 1905).

In addition to the similarities in location and symptoms, there were two other compelling pieces or evidence in support or Dr. Crohn's theory that bacterial infection caused Crohn's disease. The first was that MAP had been isolated from the intestines of Crohn's patients at much higher rates than in the general public. The second was that because of its ability to survive pasteurization, MAP was detectable in various milk products, providing plausible way for it to get from cows to humans. But what kept this from all fitting together nicely was that not everyone who had Crohn's disease has MAP. In fact, most Crohn's sufferers tested negative for MAP. So, after additional studies were unable to prove clear cause and effect, the idea that Chron's was the result of bacterial infection was mostly abandoned.

Almost a century later, we still don't know what causes autoimmune illnesses such as Crohn's , although there's been lots of speculation - from infectious like measles, E. coli, and enterovirus to lifestyle factors like smoking and stress to common and seemingly benign practices like the use of toothpaste and refrigeration. In keeping with Dr. Crohn's initial theory do indeed play a major role, but it may be their absence rather than their presence that leads to the diagnosis.

The Hygiene Hypothesis

In the late 1950s, Professor David Strachan, a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, embarked on an epidemiological study of hay fever and eczema in British children. These diseases had been steadily increasing since the turn of the century when large populations left the farm for the factory. The study followed seventeen thousand children from birth to adulthood and the results revealed a startling and unexpected association: both conditions were far less common in large families with lots of early childhood infections rom exposure to siblings. The highest rates of disease occurred in smaller family size with fewer runny-nosed microbial donors and in affluent households with loftier standards of personal hygiene. This finding was counter to everything we thought we knew about germs. Could exposure to more germs really be better for us? And could living a cleaner lifestyle be making us sicker?

In the late 1950s, Professor David Strachan, a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, embarked on an epidemiological study of hay fever and eczema in British children. These diseases had been steadily increasing since the turn of the century when large populations left the farm for the factory. The study followed seventeen thousand children from birth to adulthood and the results revealed a startling and unexpected association: both conditions were far less common in large families with lots of early childhood infections rom exposure to siblings. The highest rates of disease occurred in smaller family size with fewer runny-nosed microbial donors and in affluent households with loftier standards of personal hygiene. This finding was counter to everything we thought we knew about germs. Could exposure to more germs really be better for us? And could living a cleaner lifestyle be making us sicker?

Strachan's initial paper, titled "Hay Fever, Hygiene and Household Size," was published in the British Medical, Journal in 1989 and laid the foundation for the "hygiene hypothesis," which challenged the idea of germs as something to be avoided and posited the importance of early microbial exposure for preventing disease later in life. In 2003 Graham Rook, MD, emeritus professor or medical microbiology and immunology at University College London, expanded on this concept with his old friends hypothesis, suggesting that a lack of exposure to ancient organisms like parasites that coevolved with our ancestors, not just the absence of relatively new germs like influenza, was responsible for the emergence of these modern plagues.

If we look at a map of the world today, one of the striking observations is that illnesses like Crohn's disease are common in more developed countries and rare n less developed ones. The hygiene hypothesis accounts for this uneven distribution by suggesting that less childhood exposure to bacteria and parasites in affluent societies like the United States and Europe actually increases susceptibility to disease by suppressing the natural development of the immune system.

This concept has also been linked to the rise of many of our chronic ailments: the obesity epidemic, deadly disorders like metabolic syndrome and heart disease, psychiatric conditions like depression, poorly understood afflictions like autism, and even some forms of cancer-and clinical studies have shown significant disturbances in the microbiome in all of them. We spend huge amounts of time making sure we're clean-scrubbing ourselves with harsh soaps, sanitizing our hands and environment with chemicals, and eliminating any trace of dirt from our homes and lives-but since the evidence suggests that germs may actually be essential for our well-being, it may be time to rethink our approach to cleanliness and hygiene.

This concept has also been linked to the rise of many of our chronic ailments: the obesity epidemic, deadly disorders like metabolic syndrome and heart disease, psychiatric conditions like depression, poorly understood afflictions like autism, and even some forms of cancer-and clinical studies have shown significant disturbances in the microbiome in all of them. We spend huge amounts of time making sure we're clean-scrubbing ourselves with harsh soaps, sanitizing our hands and environment with chemicals, and eliminating any trace of dirt from our homes and lives-but since the evidence suggests that germs may actually be essential for our well-being, it may be time to rethink our approach to cleanliness and hygiene.

|

In Praise of Dirt

We need interaction with dirt and germs to rain our immune system in now to respond appropriately to stimuli in our environment - what to react to and what to ignore. An immune system that doesn't get up close and personal with enough germs early on is like a kid with overprotective parents, ill equipped to deal with problems when they inevitably happen. |

Inadequate exposure leads to defects in immune tolerance and a trigger-happy state of heightened activity where essential

bacteria, proteins in food, and even parts of our own body (the digestive tract, in the case of IBD) are treated like the enemy and attacked.

bacteria, proteins in food, and even parts of our own body (the digestive tract, in the case of IBD) are treated like the enemy and attacked.

While those living in poor countries with fewer modern conveniences are at higher risk of suffering the effects of natural disasters, poverty, and unemployment, from an autoimmune perspective there are some advantages, including much lower rates of Crohn's. Not surprisingly, as countries become more industrialized and their level of sanitation improves, the prevalence of IBD and what we might call other post-Industrial Revolution epidemics increases dramatically. It is also seen in Asia and the Middle East, where clinics devoted to Crohn's have sprung up in the last decade in regions where the disease was previously nonexistent.

There is no purpose to romanticize poverty or suggest that economic growth and development are bad things, but its worth pointing out that modern practices such as chlorinated drinking water, industrial agriculture, pesticides, sanitation, and antibiotics, whle improving our lives in many ways, have created unforeseen health challenges. Alcohol, stress, and the high-tat/high-sugar Western diet compound the problem by suppressing what essential gut flora we do have, leading to a hyperreactive immune system primed for autoimmune disease and allergies.

There is no purpose to romanticize poverty or suggest that economic growth and development are bad things, but its worth pointing out that modern practices such as chlorinated drinking water, industrial agriculture, pesticides, sanitation, and antibiotics, whle improving our lives in many ways, have created unforeseen health challenges. Alcohol, stress, and the high-tat/high-sugar Western diet compound the problem by suppressing what essential gut flora we do have, leading to a hyperreactive immune system primed for autoimmune disease and allergies.

Since our internal microbial landscape is in large part determined by our external environment, its not surprising that relocating from a less antiseptic habitat to a super-clean one, or vice versa, can alter your microbiome and trigger disease. People from less developed countries have a heightened risk for developing Crohn's and other autoimmune illnesses when they move to the United States, especially when they move at a young age.

The Role of our Genes

Many diseases that run in families that we thought were primarily genetic, such as heart disease and some forms of cancer, turn out to be hugely influenced by gut bacteria. It's the complex and poorly understood interaction among your genes, your environment and your immune system that ultimately determines whether you end up sick or not.

Epigenetics is the study of how our environment affects heritable traits without changing the actual DNA material in our

genes. It's the classic nature-versus-nurture question: how much of who we are is a result of the genes we inherit, versus the environment we live in?

What we're finding is that the environment living inside us - our microbiome - has one of the biggest impacts on our genes, turning on and off and determining which ones are ultimately expressed as disease.

Many diseases that run in families that we thought were primarily genetic, such as heart disease and some forms of cancer, turn out to be hugely influenced by gut bacteria. It's the complex and poorly understood interaction among your genes, your environment and your immune system that ultimately determines whether you end up sick or not.

Epigenetics is the study of how our environment affects heritable traits without changing the actual DNA material in our

genes. It's the classic nature-versus-nurture question: how much of who we are is a result of the genes we inherit, versus the environment we live in?

What we're finding is that the environment living inside us - our microbiome - has one of the biggest impacts on our genes, turning on and off and determining which ones are ultimately expressed as disease.

In fact, which gut bacteria you end up with may be even more important than which genes you inherit. This is an empowering way of looking at disease, since we can't change our real family, but we can change our microbial family. The vast majority of people with IBD don't have a family history of the disease or any identifiable genetic susceptibility, but that's not true tor everyone. People of Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish descent have a four- to fivefold increased risk of developing Crohn's, which is explained in part by a genetic variant that causes their immune system to overreact to gut flora. There are more than one hundred gene mutations associated with Crohn's, but gene abnormalities alone aren't enough to cause disease. It's triggers in the environment that ultimately unmask the genetic risk and lead to symptoms. were getting better at identifying those triggers and are realizing that most of them involve changes in gut bacteria. In fact, we can produce Crohn's in mice by transferring gut bacteria from affected mice to healthy, germ-free mice, confirming that the microbiome plays an important, if not causative, role.

|

Are we too Clean on the Inside?

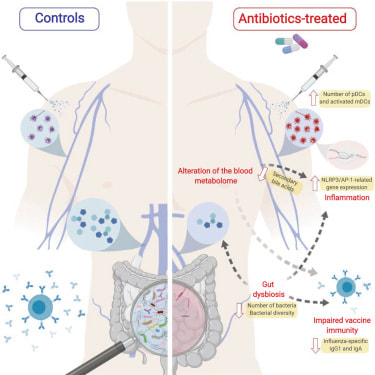

There's such a strong link between antibiotic use and digestive issues that it's literally the first question l ask new patients in my practice. But the idea that antibiotics might cause serious autoimmune illnesses like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis is a relatively new concept. It's also a troubling one, because our threshold for prescribing antibiotics is dangerously low. What's more, for decades we've been using antibiotics to treat flare-ups of these diseases! |

Could the very drugs we've so readily dispensed be part of the reason we're seeing such a dramatic increase in these modern plagues? Being treated with antibiotics in your first year of life is associated with a threefold increase in risk for IBD compared to children who haven't received antibiotics, and the risk seems to increase the more antibiotics you receive. In countries like Canada and Finland where antibiotics are widely available, the incidence of IBD in children has steadily increased about 5 percent to 8 percent annually. Studies from the United States, including a meta-analysis of more than seven thousand patients by researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital, confirm that the risk of IBD from antibiotics is highest in children, but also show an increase in new-onset Crohn's in adults who've taken antibiotics in the months before diagnosis.

All antibiotics except penicillin have been implicated, but, ironically, the ones most commonly used to treat Crohn's -metronidazole and fluoroquinolones like Ciprofloxacin-confer the highest risk.

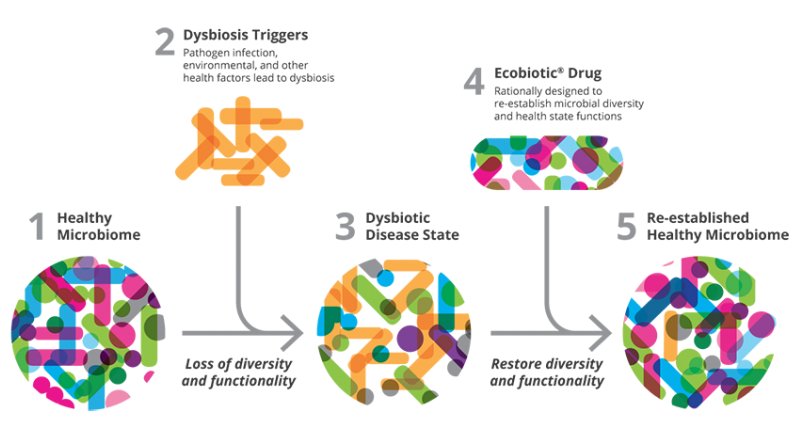

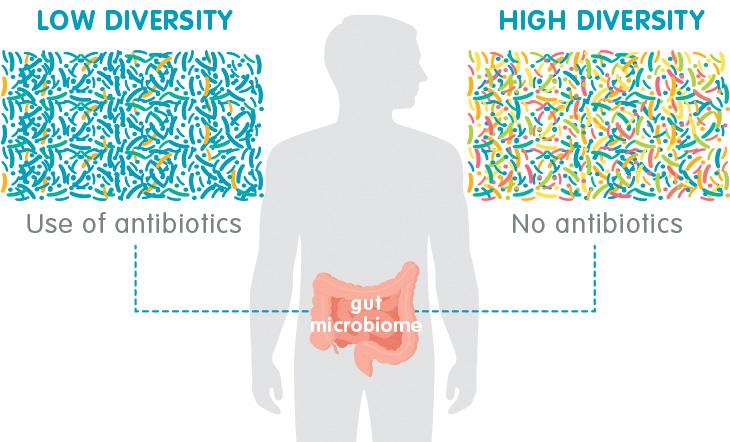

Extensive antibiotic use wipes out large amounts of bacteria, including both protective and pathogenic species. As luck would have it, the bad bacteria are often hardier than the good ones and more likely to survive the antibiotic assault. They end up multiplying and filling the gap created by the overall loss in numbers, which creates the typical profile seen in people with IBD: an overall decrease in diversity or gut bacteria, higher levels of pathogenic species, and lower levels of protective ones.

Extensive antibiotic use wipes out large amounts of bacteria, including both protective and pathogenic species. As luck would have it, the bad bacteria are often hardier than the good ones and more likely to survive the antibiotic assault. They end up multiplying and filling the gap created by the overall loss in numbers, which creates the typical profile seen in people with IBD: an overall decrease in diversity or gut bacteria, higher levels of pathogenic species, and lower levels of protective ones.

Article Review

Video on Demand Review

|

Boosting Immune System while Reducing Inflammation

|

Gut Immunology

|