Cancer Prevention & Management Unit 3

UNIT 3 |

OBJECTIVES:

REFERENCES:

- Discuss the role of lifestyle and nutrition in Cancer

- Ovarian Cancer

- Endometrial Cancer

- Cervical Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Thyroid Cancer

REFERENCES:

- Nutrition Guide for Clinicians, Neal Barnard, MD

- Nutrition and Diet Therapy Evidence-based applications, Carroll Lutz & Karen Przytulzki

Ovarian Cancer

|

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecologic cancer (after cervical cancer) and the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer in the United States. It generally affects women aged 40 to 65. The ovary is composed of epithelial cells along the surface, germ (egg-producing) cells, and surrounding connective tissue.

|

Each of these cell type has the potential for malignancy transformation. In addition, breast and gastrointestinal cancers commonly metastasize to the ovaries. The most common ovarian malignancy is epithelial carcinoma (approximately 90% of cases).

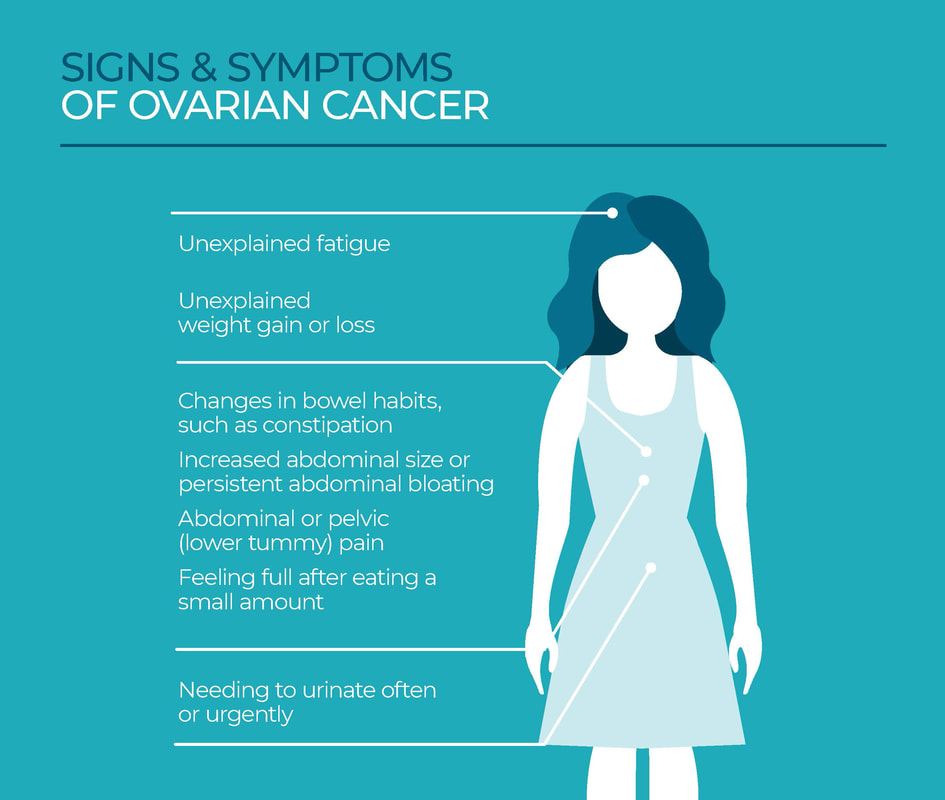

In the early stages, ovarian cancer usually causes subtle and non-specific symptoms that rarely prompt a woman to seek medical attention. More severe symptoms, often associated with ovarian torsion or rupture, are rare. As a result, only about 20% of cases are diagnosed at an early stage.

In the early stages, ovarian cancer usually causes subtle and non-specific symptoms that rarely prompt a woman to seek medical attention. More severe symptoms, often associated with ovarian torsion or rupture, are rare. As a result, only about 20% of cases are diagnosed at an early stage.

|

Nospecific symptoms may include:

|

RISK FACTORS

Possible risk factors are listed below, although the exact mechanism of induction are not clearly understood.

Possible risk factors are listed below, although the exact mechanism of induction are not clearly understood.

- Nulliparity or infertility.

- Age. Most ovarian cancers occur in women over 50 years, with the highest risk for those over 60.

- Family history. Women who have relatives with ovarian cancer have an approximately 3-fold increased risk with multiple affected relatives raising the risk further.

- BRCA gene mutation. Women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation have a 25% to 45% lifetime risk of ovarian malignancy, with BRCA1 generally presenting a higher risk.

- Race. White women have higher rates of ovarian cancer than black women.

- Previous cancer. Women with a history of breast cancer or colon cancer may have an increased risk.

- Endometriosis.

- Diet. Will be discussed next section.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATION

Epidemiologic investigation have revealed important clues to etiological factors in ovarian cancer. Mortality in both the Mediterranean region and Asia is associated with consumption of meat, milk, and animal fat. These associations have not been tested in randomized clinical trials. Nonetheless, they suggest important hypotheses regarding possible means to reduce risk.

Epidemiologic investigation have revealed important clues to etiological factors in ovarian cancer. Mortality in both the Mediterranean region and Asia is associated with consumption of meat, milk, and animal fat. These associations have not been tested in randomized clinical trials. Nonetheless, they suggest important hypotheses regarding possible means to reduce risk.

Diet and prevention of ovarian cancer. The following factors are under investigation for a possible role in reducing ovarian cancer risk.

Avoiding or reducing meat and saturated fat. A high intake of fat is associated with an approximately 25% increase risk of ovarian cancer, and most of this risk is attributed to saturated fat intake. Various food sources of saturated fat have been implicated, including meat, eggs, and whole milk. An analysis of pooled data from studies involving more than 523,000 women found a roughly 30% greater risk for ovarian cancer in women consuming the most saturated fat, compared with those consuming the lowest amount, although total fat was not associated with risk. Animal fat and meat influence estrogen activity and increase blood concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a polypeptide implicated in several cancers, including ovarian cancer.

Avoiding or reducing meat and saturated fat. A high intake of fat is associated with an approximately 25% increase risk of ovarian cancer, and most of this risk is attributed to saturated fat intake. Various food sources of saturated fat have been implicated, including meat, eggs, and whole milk. An analysis of pooled data from studies involving more than 523,000 women found a roughly 30% greater risk for ovarian cancer in women consuming the most saturated fat, compared with those consuming the lowest amount, although total fat was not associated with risk. Animal fat and meat influence estrogen activity and increase blood concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a polypeptide implicated in several cancers, including ovarian cancer.

Avoiding milk. Studies of dairy products and ovarian cancer risk have produced conflicting results and are subject for some controversy. Although some studies have not revealed a relationship, a meta-analysis of prospective study data concluded that each glass of milk consumed daily raised the risk for ovarian cancer by 13% on average. In addition, a pooled analysis of 12 prospective cohort studies including 553,217 women concluded that consumption of 3 dairy servings per day was associated with a 20% increased risk for this cancer, compared with 1 serving per day.

Saturated fat aside, even consumption of small amounts of skim or low-fat milk (1 or more servings daily) has been associated with an increased risk for ovarian cancer. This has been attributed to galactose-related oocyte toxicity and/or elevation of gonadotropin concentrations. Milk consumption also elevates IGF-1 blood concentrations. Some researchers have suggested this is due to the fact that cow's milk contains IGF-1 that is identical to the growth factor produced by humans. However, milk's macronutrients also stimulate IGF-1 production within the human body.

Increased fruit and vegetable intake. A protective effect of fruits and vegetables remains uncertain. Some studies found that women eating 3 or more vegetable servings per day had a 39% lower risk for ovarian cancer, compared with women eating 1 or fewer servings per day. However these benefits may relate only to fruit and vegetable intake during adolescence. Further, both the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study (involving more than 325,000 women) and the Netherlands Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer (involving more than 62,000 women) failed to show protective effect of high fruit and vegetable intakes.

Avoidance of obesity. Obesity in adolescence or early adulthood increases later risk for ovarian cancer by 1.5 to 2 times that of women with normal body mass index (BMI).

Avoidance of obesity. Obesity in adolescence or early adulthood increases later risk for ovarian cancer by 1.5 to 2 times that of women with normal body mass index (BMI).

DIET AND SURVIVAL AFTER OVARIAN CANCER DIAGNOSIS

A preceding studies relate to risk of developing ovarian cancer. Some studies suggest that diet may also play a role after diagnosis. The following foods are under study:

Vegetables. Women with ovarian cancer who consume vegetables rich diets tend to have enhanced survival. In population-based case-controlled study, women who consumed the most vegetables had 25% lower mortality risk, compared with women consuming the least. A similar association was found in these women for the intake of cruciferous vegetables (including broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage), and survival was inversely associated with intake of red meat, white meat, and total protein.

A preceding studies relate to risk of developing ovarian cancer. Some studies suggest that diet may also play a role after diagnosis. The following foods are under study:

Vegetables. Women with ovarian cancer who consume vegetables rich diets tend to have enhanced survival. In population-based case-controlled study, women who consumed the most vegetables had 25% lower mortality risk, compared with women consuming the least. A similar association was found in these women for the intake of cruciferous vegetables (including broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage), and survival was inversely associated with intake of red meat, white meat, and total protein.

Green tea. In a study of 254 women with histopathologically confirmed ovarian cancer followed for 3 years or more, a dose-response relationship was observed between tea intake and survival. Drinking 1 cup or more of green tea per day was associated with a 57% lower mortality. Although green tea is known to inhibit cancer growth through a variety of mechanisms in vitro and in vivo, further study is needed to assess the benefit of green tea for promoting cancer survival.

Article Review

At the end of your readings, create a reflective journal describing salient points you learned from each article. The Journal must contain the title of the Article, your name and date of submission.

Endometrial Cancer

Cancer of the endometrium, the mucus membrane lining of the uterus, accounts for 90% of uterine cancers. With nearly 40,000 new cases annually, it is the most common gynecologic cancer in the United State and the fourth most common cancer found in women. it occurs most frequently after menopause.

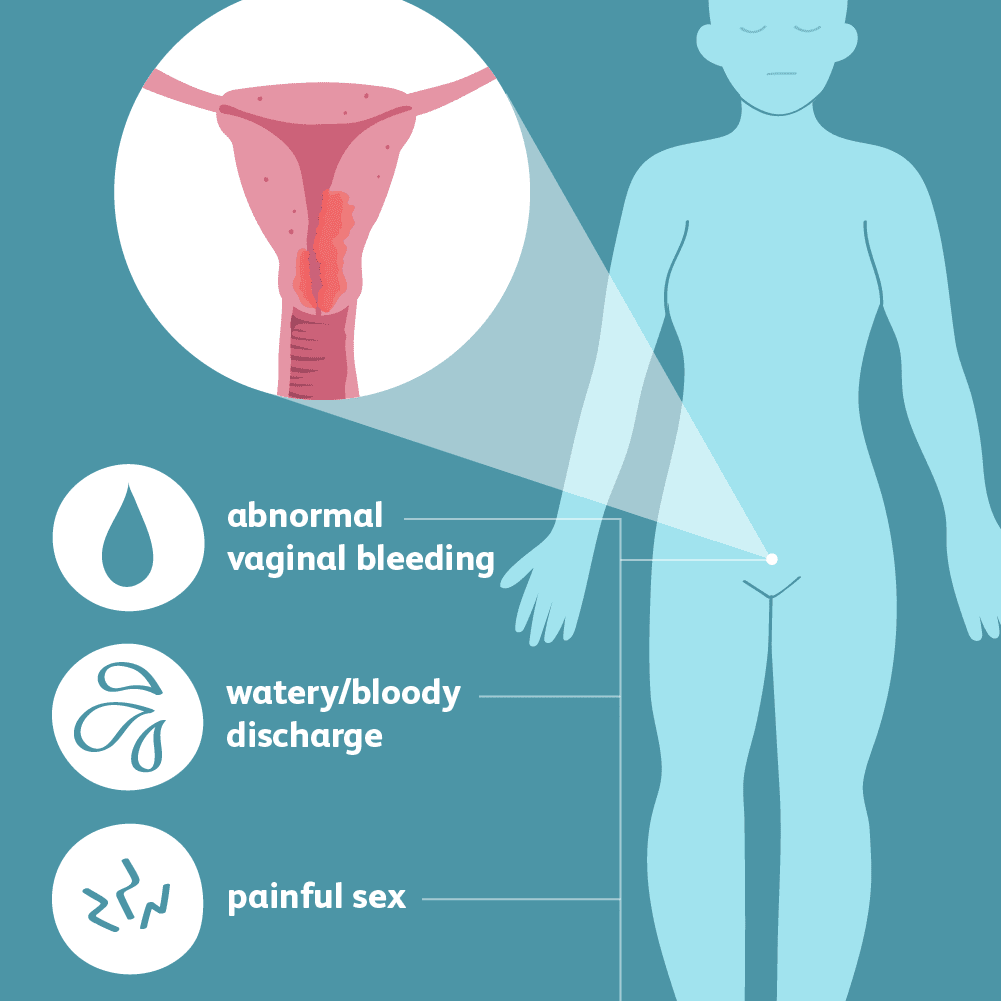

Epithelial and muscle cells of the uterus have potential for malignant transformation and constitute the 2 main histologic subtypes of uterine cancer: adenocarcinoma and sarcoma. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom of endometrial cancer, but a woman may also experience discharge, weight loss, abdominal or pelvic pain, dysuria, and/or dyspareunia. Vaginal bleeding in any postmenopausal woman should be considered uterine cancer until proven otherwise.

Most endometrial cancers are slow-growing and are discovered at an early stage. These cases can be successfully treated, usually by hysterectomy, with better than 90% cure rates. Advanced cases that spread beyond the uterus are often fatal.

The underlying cause is unknown, but estrogen likely plays a central role. Type 1 endometrial carcinomas demonstrate a response to estrogen, whereas type 2 carcinomas do not. Because type 2 tumors lack well-identified risk factors.

The underlying cause is unknown, but estrogen likely plays a central role. Type 1 endometrial carcinomas demonstrate a response to estrogen, whereas type 2 carcinomas do not. Because type 2 tumors lack well-identified risk factors.

RISK FACTORS

Obesity. A majority of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer at a young age are obese. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study including over 220,000 women found a nearly 80% greater risk for obese women, compared with those of normal weight. Risk increased by 300% in women who were morbidly obese (BMI >40). Other studies have reached similar conclusions. The relationship between obesity and cancer may be explained by obesity-related elevations in sex steroid hormones and growth factors. Peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogen in adipose tissue leads to greater endogenous estrogen concentrations in obese persons.

Obesity. A majority of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer at a young age are obese. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study including over 220,000 women found a nearly 80% greater risk for obese women, compared with those of normal weight. Risk increased by 300% in women who were morbidly obese (BMI >40). Other studies have reached similar conclusions. The relationship between obesity and cancer may be explained by obesity-related elevations in sex steroid hormones and growth factors. Peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogen in adipose tissue leads to greater endogenous estrogen concentrations in obese persons.

|

Age. Risk increases with age, and the disease generally affects women over 50 years.

Menopausal Estrogen Therapy. Unopposed estrogen increases risk but the combined use of estrogen and progestin is not associated with increased risk. Diabetes. Hypertension. Physical Inactivity. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Anovulation from PCOS or other causes results in persistent exposure to unopposed endogenous estrogen. |

Prolonged exposure to estrogen. Early menarche, late menopause, and nulliparity (especially when due to anovulation) may increase the risk.

Genetics. A family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer greatly increases the risk.

Estrogen-secreting tumors or history of estrogen-responsive cancer.

Decreased sex-hormone binding globulin levels.

Tamoxifen use. There is an increased risk in women using tamoxifen as therapy of breast cancer.

Oral contraceptive use, multiparity, and exercise are considered protective.

Genetics. A family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer greatly increases the risk.

Estrogen-secreting tumors or history of estrogen-responsive cancer.

Decreased sex-hormone binding globulin levels.

Tamoxifen use. There is an increased risk in women using tamoxifen as therapy of breast cancer.

Oral contraceptive use, multiparity, and exercise are considered protective.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

As with many cancers, the risk for uterine cancers appears to be associated with greater intakes of foods found in Western diets (animal products, refined carbohydrates). Risk may be lower among women whose diets are high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.

The lower risk in persons eating plant-based diets may be related to a reduced amount of free hormones circulating in the blood or to a protective effect of micronutrients found in these diets. The following factors are under study for possible protective effects:

Eating less meat and fat. One study found a 50% greater risk of endometrial cancer among women who consumed the greatest amount of processed meat and fish. Another found that consumption of red meat and eggs is also associated with greater endometrial cancer risk. Overall, case-control studies have identified increased risk of endometrial cancer associated with intake of meat, particularly red meat, a finding not reflected in most prospective studies.

Higher intake of fat, particularly saturated fat, is associated with elevations of endometrial cancer risk of approximately 60% to 80%. Some evidence indicates that this association is due to the influence of dietary fat on adiposity and, consequently, on circulating estrogens.

Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Available evidence suggests that vegetables, fruits, and the nutrients these foods contain (ie, vitamin C, various carotenoids, folate, phytosterols) may be associated with reduced risk of endometrial cancer. The hypothesized risk reduction may be as high as 50% to 60%. In the American Cancer Society's

Cancer Prevention Study Il Nutrition Cohort of over 41,000 women, protective effects of vegetables and fruits (20% and 25% lower risk, respectively) were identified only in women who had both never used hormone therapy and were consuming the largest amounts of these foods. Inverse association between whole grain intake and endometrial cancer has been observed, although some data suggest that this benefit may be restricted to women who have never used hormones. Higher intakes of soy and other legumes may also decrease risk.

As with many cancers, the risk for uterine cancers appears to be associated with greater intakes of foods found in Western diets (animal products, refined carbohydrates). Risk may be lower among women whose diets are high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.

The lower risk in persons eating plant-based diets may be related to a reduced amount of free hormones circulating in the blood or to a protective effect of micronutrients found in these diets. The following factors are under study for possible protective effects:

Eating less meat and fat. One study found a 50% greater risk of endometrial cancer among women who consumed the greatest amount of processed meat and fish. Another found that consumption of red meat and eggs is also associated with greater endometrial cancer risk. Overall, case-control studies have identified increased risk of endometrial cancer associated with intake of meat, particularly red meat, a finding not reflected in most prospective studies.

Higher intake of fat, particularly saturated fat, is associated with elevations of endometrial cancer risk of approximately 60% to 80%. Some evidence indicates that this association is due to the influence of dietary fat on adiposity and, consequently, on circulating estrogens.

Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Available evidence suggests that vegetables, fruits, and the nutrients these foods contain (ie, vitamin C, various carotenoids, folate, phytosterols) may be associated with reduced risk of endometrial cancer. The hypothesized risk reduction may be as high as 50% to 60%. In the American Cancer Society's

Cancer Prevention Study Il Nutrition Cohort of over 41,000 women, protective effects of vegetables and fruits (20% and 25% lower risk, respectively) were identified only in women who had both never used hormone therapy and were consuming the largest amounts of these foods. Inverse association between whole grain intake and endometrial cancer has been observed, although some data suggest that this benefit may be restricted to women who have never used hormones. Higher intakes of soy and other legumes may also decrease risk.

Some whole grains and most legumes have a low glycemic index (a ranking of carbohydrate-containing foods based on the food's effect on blood sugar compared with a standard reference food's effect). Women whose diets had the most high-glycemic index foods had a roughly 50% greater risk for endometrial cancer than those whose diets had the

lowest amount of these foods. Among obese women (BMI >30), the risk for endometrial cancer in those eating the most high-glycemic index foods was increased by roughly 90%. Among nondiabetic women, those whose diets were highest in glycemic load (glycemic index of a food times the number of grams of carbohydrates in the food serving)

had a roughly 45% greater risk for endometrial cancer.

Moderating alcohol consumption. Studies on alcohol intake and risk for uterine cancer have produced conflicting results, with various studies finding no association, a protective effect, or increased risk. The Multiethnic Cohort Study of 41,574 women found a significantly greater risk (twice that of non-drinkers) in those having 2 or more alcoholic beverages daily. However, the Netherlands Cohort Study of 62,573 women found no evidence of increased risk associated alcohol use.

lowest amount of these foods. Among obese women (BMI >30), the risk for endometrial cancer in those eating the most high-glycemic index foods was increased by roughly 90%. Among nondiabetic women, those whose diets were highest in glycemic load (glycemic index of a food times the number of grams of carbohydrates in the food serving)

had a roughly 45% greater risk for endometrial cancer.

Moderating alcohol consumption. Studies on alcohol intake and risk for uterine cancer have produced conflicting results, with various studies finding no association, a protective effect, or increased risk. The Multiethnic Cohort Study of 41,574 women found a significantly greater risk (twice that of non-drinkers) in those having 2 or more alcoholic beverages daily. However, the Netherlands Cohort Study of 62,573 women found no evidence of increased risk associated alcohol use.

Article Review

At the end of your readings, create a reflective journal describing salient points you learned from each article. The Journal must contain the title of the Article, your name and date of submission.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer occurs primarily in 2 varieties: squamous cell carcinoma (about 80% of cases) and adenocarcinoma (about 15%). Adenosquamous carcinoma makes up most of the remaining cases, and this type may have a poorer outcome. Since the inception of annual Pap smear screening, there has been a marked decline in cervical cancer incidence. The majority of cases now occur in women who have not been adequately screened. Due in part to the success of such screening programs, cervical cancer only accounts for about 1% of all cancer deaths in developed countries. Cervical cancer is age-related; incidence is extremely low in women under 20 and peaks in women

45 to 49.

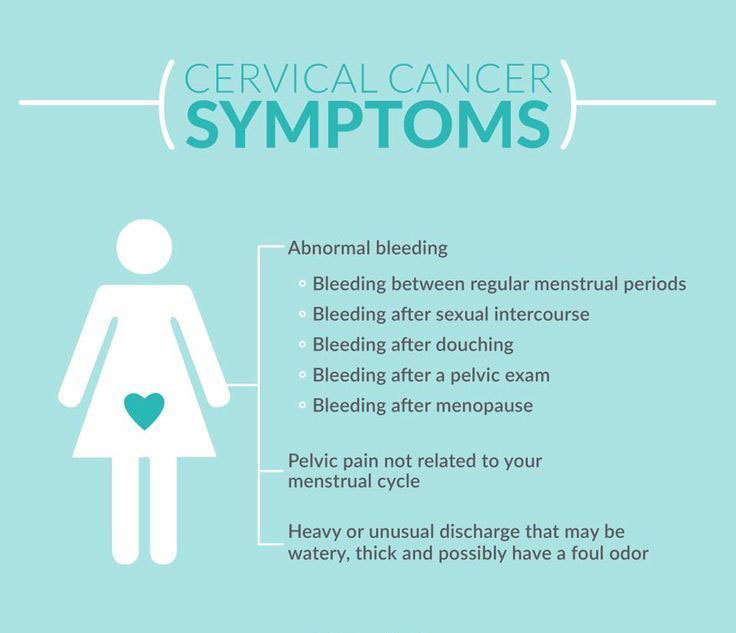

Symptoms are absent in many cases, but abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding often occurs. Advanced disease may also cause pain in the low back and pelvis with radiation into the posterior legs, as well as bowel or urinary symptoms, such as passage of blood and a sensation of pressure.

In 2006, the FDA approved Gardasil, a recombinant vaccine that protects against 4 strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) that are implicated in up to 70% of cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, a precursor to cervical cancer, and 90% of cases of female genital warts. However, the vaccine does not protect against cervical cancer among those already infected with HPV, and it does not influence risk of cases not due to these HPV strains.

45 to 49.

Symptoms are absent in many cases, but abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding often occurs. Advanced disease may also cause pain in the low back and pelvis with radiation into the posterior legs, as well as bowel or urinary symptoms, such as passage of blood and a sensation of pressure.

In 2006, the FDA approved Gardasil, a recombinant vaccine that protects against 4 strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) that are implicated in up to 70% of cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, a precursor to cervical cancer, and 90% of cases of female genital warts. However, the vaccine does not protect against cervical cancer among those already infected with HPV, and it does not influence risk of cases not due to these HPV strains.

|

RISK FACTORS

Women in developing nations have much higher mortality (nearly 50%), compared with those in developed nations due to the scarcity of screening programs. Other risk factors include: Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. This virus has many sub-types and not all cause cancer, but most cervical cancers involve HPV. High-risk HPV includes types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, and 45. |

Sexual factors. Early sexual intercourse, history of multiple sexual partners for a partner with multiple partners), history of sexually transmitted disease, sexual relationship with a person who has exposure HPV, and intercourse with an uncircumcised man are associated with increased risk. Uncircumcised men and their sexual partners nave elevated rate of HPV infection.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Epidemiologic studies suggest that dietary factors may influence risk for cervical cancer. Part of the effect of diet may be attributable to the suppressive action of certain micronutrients on HPV infection, particularly carotenoids (both vitamin A and non-vitamin A precursors), folate, and vitamins C and E. The following factors have been associated with

reduced risk:

Fruits and vegetables. A systematic review of evidence linking fruits, vegetables, and some of their bioactive components to protection against cervical cancer graded the evidence as "possible" for vegetables, vitamin C, and many carotenoids (eg, alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin, and cryptoxanthin). A possible protective effect against HPV persistence was also determined for the intake of fruits, vegetables, vitamins C and E, and the carotenoids mentioned above. Evidence was also noted as "probable" for retinol and vitamin E, as well as for the roles of folate and homocysteine, in cervical neoplasia.

Folic acid and other B vitamins. Interactions appear to exist between folate status, mutations in the folate-dependent enzyme methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), plasma homocysteine, and HPV that may reduce cervical cancer risk. Lower red blood cell levels of folate have been associated with a 5-fold greater risk for HPV-related cervical dysplasia. A combination of factors that increase folate requirement (MTHFR polymorphism and pregnancy) was associated with a 23-fold greater risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, compared with the risk in nulliparous women with the normal MTHFR genotype.

Blood levels of homocysteine may increase with the MTHFR genotype, and hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with a 2.5-to-3 times greater risk for invasive cervical cancer." HPV increases the risk for cervical neoplasia almost 5-fold, above a homocysteine level of roughly 9 umol/L. Other studies showed that circulating levels of vitamin B12 were inversely associated with HPV persistence, and that B12 supplements were inversely associated with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix.

Food sources of vitamin E. The review cited above describes evidence of a protective effect of high blood levels of vitamin E as possible" for HPV persistence and probable" for cervical neoplasia. In addition, obese women appear to have a modestly higher risk for cervical adenocarcinoma, which represents 15% of cervical cancers. Mortality from cervical cancer overall is also increased in obese patients. While an important body of research on diet and cervical cancer risk exists, there has been little research on the role of diet in survival after diagnosis.

Epidemiologic studies suggest that dietary factors may influence risk for cervical cancer. Part of the effect of diet may be attributable to the suppressive action of certain micronutrients on HPV infection, particularly carotenoids (both vitamin A and non-vitamin A precursors), folate, and vitamins C and E. The following factors have been associated with

reduced risk:

Fruits and vegetables. A systematic review of evidence linking fruits, vegetables, and some of their bioactive components to protection against cervical cancer graded the evidence as "possible" for vegetables, vitamin C, and many carotenoids (eg, alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin, and cryptoxanthin). A possible protective effect against HPV persistence was also determined for the intake of fruits, vegetables, vitamins C and E, and the carotenoids mentioned above. Evidence was also noted as "probable" for retinol and vitamin E, as well as for the roles of folate and homocysteine, in cervical neoplasia.

Folic acid and other B vitamins. Interactions appear to exist between folate status, mutations in the folate-dependent enzyme methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), plasma homocysteine, and HPV that may reduce cervical cancer risk. Lower red blood cell levels of folate have been associated with a 5-fold greater risk for HPV-related cervical dysplasia. A combination of factors that increase folate requirement (MTHFR polymorphism and pregnancy) was associated with a 23-fold greater risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, compared with the risk in nulliparous women with the normal MTHFR genotype.

Blood levels of homocysteine may increase with the MTHFR genotype, and hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with a 2.5-to-3 times greater risk for invasive cervical cancer." HPV increases the risk for cervical neoplasia almost 5-fold, above a homocysteine level of roughly 9 umol/L. Other studies showed that circulating levels of vitamin B12 were inversely associated with HPV persistence, and that B12 supplements were inversely associated with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix.

Food sources of vitamin E. The review cited above describes evidence of a protective effect of high blood levels of vitamin E as possible" for HPV persistence and probable" for cervical neoplasia. In addition, obese women appear to have a modestly higher risk for cervical adenocarcinoma, which represents 15% of cervical cancers. Mortality from cervical cancer overall is also increased in obese patients. While an important body of research on diet and cervical cancer risk exists, there has been little research on the role of diet in survival after diagnosis.

Article Review

At the end of your reading, create a reflective journal describing salient points you learned from the article. The Journal must contain the title of the Article, your name and date of submission.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death for men and women worldwide. It is the most frequently occurring cancer in men and the third most frequent in women. Lung cancer usually develops within the epithelium of the bronchial tree and subsequently invades the pulmonary parenchyma. In advanced stages, it invades surrounding organs and may metastasize throughout the body.

RISK FACTORS

Smoking. Tobacco smoking accounts for approximately 90% of lung cancers. Initially, tobacco smoke irritates the bronchial epithelium and paralyzes the respiratory cilia, depriving the respiratory mucosa of its defense and clearance mechanisms. The carcinogens in tobacco smoke then act on the epithelium, giving rise to atypical cells, which form the first stage of cancer; carcinoma in situ. After metaplastic transformation, the cancer invades bronchial and pulmonary tissues and subsequently metastasizes hematogenously or via lymphatics.

Passive smoking. Epidemiologic evidence suggest an increased risk of approximately 20% to 25% in nonsmokers regularly exposed to secondary smoke.

Occupation. Exposure to manipulated asbestos, chromium and nickel (heavy metals), benzopyrene, acroleine, nitrous monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde, nicotine, radioactive lead, carbon monoxide, insecticides or pesticides containing arsenic, glass fibers, and coal dust increases workers' risk of bronchopulmonary cancer.

Family history. Investigations show a 14-fold higher frequency of lung carcinomas in smokers with a family history of lung cancer. Risk is also increased in individuals with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, resulting from an inherited mutation in the p53 gene.

Immunosuppression. The risk of oncogenesis increases with conditions that weaken the immune system (immunosuppressive medications, diseases, or malnutrition).

Air-pollution. The mortality rate from lung cancer is 2 to 5 times higher in industrialized areas than in less polluted rural areas.

Inflammation. Chronic and recurrent respiratory diseases act as chronic irritants and play an oncogenic role (eg. tuberculosis,, chronic bronchitis, recurrent penumonias).

Ionizing radiation. Radiation exposure (x-rays, radon gas) increases carcinogenic risk in a dose-dependent manner. Lung cancer is 10 times more frequent in uranium miners than in the general population.

Diet and Nutrition. Will be discussed in the next section.

Smoking. Tobacco smoking accounts for approximately 90% of lung cancers. Initially, tobacco smoke irritates the bronchial epithelium and paralyzes the respiratory cilia, depriving the respiratory mucosa of its defense and clearance mechanisms. The carcinogens in tobacco smoke then act on the epithelium, giving rise to atypical cells, which form the first stage of cancer; carcinoma in situ. After metaplastic transformation, the cancer invades bronchial and pulmonary tissues and subsequently metastasizes hematogenously or via lymphatics.

Passive smoking. Epidemiologic evidence suggest an increased risk of approximately 20% to 25% in nonsmokers regularly exposed to secondary smoke.

Occupation. Exposure to manipulated asbestos, chromium and nickel (heavy metals), benzopyrene, acroleine, nitrous monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde, nicotine, radioactive lead, carbon monoxide, insecticides or pesticides containing arsenic, glass fibers, and coal dust increases workers' risk of bronchopulmonary cancer.

Family history. Investigations show a 14-fold higher frequency of lung carcinomas in smokers with a family history of lung cancer. Risk is also increased in individuals with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, resulting from an inherited mutation in the p53 gene.

Immunosuppression. The risk of oncogenesis increases with conditions that weaken the immune system (immunosuppressive medications, diseases, or malnutrition).

Air-pollution. The mortality rate from lung cancer is 2 to 5 times higher in industrialized areas than in less polluted rural areas.

Inflammation. Chronic and recurrent respiratory diseases act as chronic irritants and play an oncogenic role (eg. tuberculosis,, chronic bronchitis, recurrent penumonias).

Ionizing radiation. Radiation exposure (x-rays, radon gas) increases carcinogenic risk in a dose-dependent manner. Lung cancer is 10 times more frequent in uranium miners than in the general population.

Diet and Nutrition. Will be discussed in the next section.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Although environmental exposures (particularly tobacco smoke and, to a lesser extent, air pollution, asbestos and radon) are the chief causes of lung cancer, diet plays a surprisingly important role. Research on the relationships between diet, smoking, and lung cancer risk is complicated by the fact that smokers tend to have lower intakes and/or lower blood levels of many protective nutrients, compared with non-smokers. Nonetheless, certain patterns have emerged.

Overall, evidence suggests that individuals (eg, Seventh-day Adventists) eating plant0based diets rich in vegetables and fruits may be at lower risk for lung cancer, independent of tobacco use. The aspects of the diet associated with reduced risk are avoiding meat and saturated fat, consuming antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables, and limiting alcohol.

Avoiding meat and saturated fat. Some studies suggest that vegetarians are associated with lower risk for lung cancer. Increased risk is also associated with regular consumption of red meat, particularly ham, sausage, and liver, saturated fat, and dairy products. The NIH_AARP study of more than 500,000 individuals found a 20% greater risk for lung cancer in persons eating the most red meat (approximately 60g/d) compared with those eating least (10g/d).

Consumption of fruits and vegetables. Several studies show that individuals with diets rich in vegetables and fruits have reduced risk for lunch cancer, independent of smoking. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC) study more than 478,000 individuals found inverse associations between fruit intake and lung cancer in non-smokers, in addition to inverse associations between vegetable intake and lung cancer in smokers.

Although environmental exposures (particularly tobacco smoke and, to a lesser extent, air pollution, asbestos and radon) are the chief causes of lung cancer, diet plays a surprisingly important role. Research on the relationships between diet, smoking, and lung cancer risk is complicated by the fact that smokers tend to have lower intakes and/or lower blood levels of many protective nutrients, compared with non-smokers. Nonetheless, certain patterns have emerged.

Overall, evidence suggests that individuals (eg, Seventh-day Adventists) eating plant0based diets rich in vegetables and fruits may be at lower risk for lung cancer, independent of tobacco use. The aspects of the diet associated with reduced risk are avoiding meat and saturated fat, consuming antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables, and limiting alcohol.

Avoiding meat and saturated fat. Some studies suggest that vegetarians are associated with lower risk for lung cancer. Increased risk is also associated with regular consumption of red meat, particularly ham, sausage, and liver, saturated fat, and dairy products. The NIH_AARP study of more than 500,000 individuals found a 20% greater risk for lung cancer in persons eating the most red meat (approximately 60g/d) compared with those eating least (10g/d).

Consumption of fruits and vegetables. Several studies show that individuals with diets rich in vegetables and fruits have reduced risk for lunch cancer, independent of smoking. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC) study more than 478,000 individuals found inverse associations between fruit intake and lung cancer in non-smokers, in addition to inverse associations between vegetable intake and lung cancer in smokers.

Nutrients that appear responsible for these protective benefits include carotenoids (as opposed to vitamin A found in animal products); vitamin C, sulfur compounds in cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage), flavonoids, and folic acid. A comprehensive antioxidant index that summarized the collective intake of carotenoids, flavonoids, vitamins E and C, and selenium among male smokers found that those with the highest antioxidant consumption had a significantly lower risk for lung cancer than those with the lowest antioxidant intakes. These appears to be no decrease in lung cancer incidence in persons taking antioxidant supplements, with the exception of individuals with poor selenium status who take selenium supplements. Beta-carotene supplements may actually raise lung cancer risk, at least in certain subgroups.

Limiting alcohol intake. Several studies suggest that regular intake of higher amounts of beer and spirits increases lung cancer risk up to 3 times that of nondrinkers. In the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), high chronic alcohol intake (> 60 g/d, about 5 drinks) was associated with a roughly 30% greater lung cancer risk when compared with low intake (0.1 to 4.9 g/d; 1 drink or less each day). However, moderate alcohol intakes (5 to 15 g/d; 1 drink or less each day) were associated with a roughly 20% to 25% lower risk for lung cancer, a finding also noted in prior studies.

It remains unclear whether these associations represent cause and effect. The link between high alcohol intake and lung cancer may reflect an association with smoking or a carcinogenic effect of acetaldehyde, an alcohol metabolite, and the ability of alcohol to activate carcinogens through an increase in cytochrome P450. The hypothetical basis for a protective effect of moderate alcohol use may be anti-inflammatory actions, antioxidant components or alcoholic beverages (flavonoids in red wine and beer), and/or induction of DNA repair enzymes or carcinogen detoxification enzymes.

Article Review

At the end of your reading, create a reflective journal describing salient points you learned from the article. The Journal must contain the title of the Article, your name and date of submission.

Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid cancers are uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers. However, incidence has risen significantly during the past half century, possibly the result of radiation therapy to the head and neck used to treat benign childhood conditions in the mid-1900s.

Patients usually present with a solitary thyroid nodule. Although most nodules are benign, all patients with a thyroid nodule should be evaluated for thyroid cancer. Associated symptoms that raise suspicion for thyroid cancer include hoarseness, dysphagia or odynophagia, and adenopathy.

Patients usually present with a solitary thyroid nodule. Although most nodules are benign, all patients with a thyroid nodule should be evaluated for thyroid cancer. Associated symptoms that raise suspicion for thyroid cancer include hoarseness, dysphagia or odynophagia, and adenopathy.

The majority of thyroid cancers are papillary or follicular carcinomas. Medullary carcinomas are well-differentiated tumors that respond well to treatment. with cure rates exceeding 90%. Medullary carcinoma, which accounts for just 5% of cases, is a cancer of the calcitonin-producing C cells of the thyroid and may be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2) syndromes. Anaplastic carcinoma is a rare but aggressive cancer with a poor prognosis.

RISK FACTORS

Female gender. Nearly three-fourths of thyroid malignancies occur in women, making this cancer the eight most common female malignancy.

Radiation exposure. Head and neck radiation, especially during infancy, is a strong risk factor for all thyroid cancers.

Genetics. Relatives of thyroid cancer patients have 10-fold greater risk. In addition, medullary carcinoma may be inherited, either as part of MEN 2 syndromes or as an isolated familial disease. Rearrangements of the RET and TRK genes are found in some papillary carcinomas.

Overweight. Excess weight may increase the risk for thyroid cancer. A study of approximately 2 million individuals in Norway who were followed for 23 years indicated that obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) was associated with thyroid cancer incidence. Specifically, risk in women in BMI categories 30 to 34.0 to 39.9 and >40 increased by 27%, 33% and 38% respectively, compared with risk in women with a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9. A similar increase was found in risk for men with a BMI >30.

Female gender. Nearly three-fourths of thyroid malignancies occur in women, making this cancer the eight most common female malignancy.

Radiation exposure. Head and neck radiation, especially during infancy, is a strong risk factor for all thyroid cancers.

Genetics. Relatives of thyroid cancer patients have 10-fold greater risk. In addition, medullary carcinoma may be inherited, either as part of MEN 2 syndromes or as an isolated familial disease. Rearrangements of the RET and TRK genes are found in some papillary carcinomas.

Overweight. Excess weight may increase the risk for thyroid cancer. A study of approximately 2 million individuals in Norway who were followed for 23 years indicated that obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) was associated with thyroid cancer incidence. Specifically, risk in women in BMI categories 30 to 34.0 to 39.9 and >40 increased by 27%, 33% and 38% respectively, compared with risk in women with a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9. A similar increase was found in risk for men with a BMI >30.

DIAGNOSIS

Evaluation should begin with thyroid function test, including thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroxin, to check for hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is the best diagnostic test and will establish the diagnosis in most cases.

Ultrasound may detect nodules and distinguish solid from cystic lesions.

Radioactive iodine uptake scan (thyroid scintigraphy) evaluates whether a nodule takes up iodine to distinguish functioning thyroid nodule (those that produce thyroid hormone) from nonfunctioning nodules. Functioning nodules are rarely malignant. Nonfunctioning nodules may be malignant and require a fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

Serum calcitonin concentration may be elevated in medullary carcinomas.

Evaluation should begin with thyroid function test, including thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroxin, to check for hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is the best diagnostic test and will establish the diagnosis in most cases.

Ultrasound may detect nodules and distinguish solid from cystic lesions.

Radioactive iodine uptake scan (thyroid scintigraphy) evaluates whether a nodule takes up iodine to distinguish functioning thyroid nodule (those that produce thyroid hormone) from nonfunctioning nodules. Functioning nodules are rarely malignant. Nonfunctioning nodules may be malignant and require a fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

Serum calcitonin concentration may be elevated in medullary carcinomas.

TREATMENT

Thyroidectomy is the primary therapy for most thyroid cancers. Resection is often followed by postoperative radioactive iodine ablation of residual thyroid tissue and potential metastases.

Lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy is necessary for all surgical patients. Treatment may include radiation and chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery or for palliation, primarily for patients with medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Thyroidectomy is the primary therapy for most thyroid cancers. Resection is often followed by postoperative radioactive iodine ablation of residual thyroid tissue and potential metastases.

Lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy is necessary for all surgical patients. Treatment may include radiation and chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery or for palliation, primarily for patients with medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

In epidemiologic studies certain dietary patterns are associated with reduced risk for thyroid cancer. As noted above, obesity increases risk. As is the case with many other types of cancer, eating more fruits and vegetables, avoiding animal fat, and replacing animal products with plant-based foods appear to have a protective effect.

In epidemiologic studies certain dietary patterns are associated with reduced risk for thyroid cancer. As noted above, obesity increases risk. As is the case with many other types of cancer, eating more fruits and vegetables, avoiding animal fat, and replacing animal products with plant-based foods appear to have a protective effect.

Avoiding animal products. Persons who consume large amounts of butter and cheese have 2.1-fold and 1.4-fold higher risk for thyroid cancer respectively, than those who consume small amounts of these foods. High intakes of processed fish products and chicken were associated with roughly double the risk by about 1.6-fold. Retinol, a form of vitamin A obtained from animal products, including eggs and milk, increased the risk for thyroid carcinoma 1.5-fold in persons with the highest intakes compared with the risk in those who had the lowest intakes.

Increasing vegetables and fruits. A diet that includes large amount of fruits and vegetables appears to reduce thyroid cancer risk by roughly 10% to 30%. Individuals with higher intake of beta-carotene appear to have half the risk for thyroid cancer compared with persons with the lowest intake.

In addition, it may be that certain components of a traditional Asian diet lower the risk for thyroid cancer. Studies have found that cancer and other thyroid diseases occur more often among Asian immigrants to the United States than among Asians in their native countries. The explanation may relate not only to the relative scarcity of animal products in an Asian diet compared with a Western diet, but also to the inclusion of soy and tea. When comparing lowest with highest intakes of soy foods, women consuming the greatest amount had a 30% to 44% lower risk for thyroid cancer. Tea consumption (>3 cups/day), another characteristic of traditional Asian diets, conferred a 70% lower risk for thyroid cancer in women

In addition, it may be that certain components of a traditional Asian diet lower the risk for thyroid cancer. Studies have found that cancer and other thyroid diseases occur more often among Asian immigrants to the United States than among Asians in their native countries. The explanation may relate not only to the relative scarcity of animal products in an Asian diet compared with a Western diet, but also to the inclusion of soy and tea. When comparing lowest with highest intakes of soy foods, women consuming the greatest amount had a 30% to 44% lower risk for thyroid cancer. Tea consumption (>3 cups/day), another characteristic of traditional Asian diets, conferred a 70% lower risk for thyroid cancer in women

Article Review

At the end of your reading, create a reflective journal describing salient points you learned from the article. The Journal must contain the title of the Article, your name and date of submission.

Common Nutrient Problems in Cancer Patients

Once a person has cancer, nutrition becomes part of the treatment. Despite the possible role of diet in preventing cancer, dietary manipulation has not been shown to cure cancer. The dietary goal is to maintain the client's strength to endure the treatment of the cancer. Energy needs based on body weight are 25 to 35 kcal/kg/day including 1 to 2g/kg/day of protein (Wilkes, 2000). A study in Germany found 24.2 percent of hospitalized clients to be malnourished, with significantly higher prevalence in those with malignant disease and older clients. Malnourished clients also had 40 percent longer hospital stays (Pirlich et al, 2003). Optimal nutrition may enhance medical treatment, associated with other diseases, including AIDS, alcoholism, heart failure, malaria, rheumatoid arthritis, and tuberculosis. The client loses weight involving both adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, but the wasting is not due to malnutrition, which preferentially depletes lipids from adipose tissue. Overall skeletal muscle protein breakdown rates in cancer patients have not been found to be different from controls, but the rate of muscle protein synthesis is reduced, thereby producing net muscle protein loss.

In cancer, cachexia occurs, despite efforts to nourish the client, because of the tumor's effects on the client's metabolism in which increased resting energy expenditure can occur despite the reduced dietary intake, indicating a malfunction of metabolism that rarely can be explained by the actual energy demands of the tumor. Several substances produced by the tumor have been identified as mediators of tissue wasting in cachexia. A lipid- mobilizing factor stimulates lipolysis and increases energy expenditure. Cachexia-inducing tumors also produce a chemical that causes protein catabolism in skeletal muscle, while visceral protein is preserved. Of particular relevance to nutrition is that a polyunsaturated fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), weakens the activity of this proteolytic-inducing factor and prevents loss of skeletal muscle.

ASSESSMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Cancer also changes the client's carbohydrate metabolism. Insulin resistance is common. The client can no longer produce glucose efficiently from carbohydrate but instead uses tissue protein for energy. In traumatized non-cancer clients, catabolism of fat for fuel gradually replaces protein breakdown, but the cancer client's body does not make this adaptive change. Another likely causative factor in cachexia is the body's inflammatory response to the tumor. Treatment with anti-

inflammatory drugs seems to have an anabolic effect.

Unexplained weight loss is one of the seven danger signals of cancer, but it is not a universal sign. Compared to 80 percent of clients with cancers of the stomach and pancreas who experienced weight loss, just 31 to 40 percent of those with breast or hematologic cancers or sarcomas and 54 to 64 percent of those with cancers of the colon, lung, and prostate were so affected. Anorexia and changes in the sense of taste often precede the diagnosis of cancer. Because the tumor alters the person's metabolism, it is possible for weight loss to occur without a reduction in food intake. Involuntary weight loss of more than 10 percent is associated with poorer survival rates, and percentage of weight loss is a sensitive and specific tool that can effectively screen and identify malnutrition in cancer clients. In addition, compared to 10 percent of those remaining disease free, unexplained weight loss occurred in 84 percent of breast cancer clients who developed recurrences, and the weight loss preceded the diagnosis of recurrence by 4 to 12 months. As cancer clients often develop ascites as well as other third-space sequestering of fluids, interpreting the weight gain or loss may be difficult. Nevertheless, weight is an important measure of progress in treating ascites.

Serum proteins, particularly albumin, reflect skeletal muscle and visceral protein status. Increased breakdown of the body's tissues and catabolism of the albumin produces low serum albumin levels. Hypoalbuminemia also may be caused by nephrotic syndrome or loss of proteins from removal of third-space fluids. Serum transferrin is also used as a marker for protein status. Because its half-life is 8 days, compared with 20 days for albumin, serum transferrin levels reflect the client's responses to stress or to nutritional support faster than serum albumin levels.

Some nutritional problems in cancer clients are due to the disease, and others are due to treatment modalities. Common problems affecting the consumption of meals and nourishment of cancer clients are early satiety and anorexia, taste alterations, local effects in the mouth, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, and altered immune response.

Early Satiety and Anorexia

Although they may look starved, cancer clients may take a few bites of food and declare that they are full. They may say that they have no appetite at all. The main source of this symptom is the cancer itself, by mechanisms that are beginning to be understood. Control of the disease improves the appetite. Sometimes, though, the physical pressure from the tumor or third-space fluid accumulation may give a feeling of fullness. Relieving that problem may improve food intake.

Some additional factors may interfere with appetite. The psychological stress of dealing with cancer may produce anxiety or depression. The person may be grappling with a body image change or may be going through the grieving process for the loss of a body function or the potential loss of life itself.

Taste Alterations

Cancer patients often have changes in taste perceptions, particularly a decreased threshold for bitterness. Accordingly, they will often say that beef and pork taste bitter or metallic. Some clients report a decreased sensation of sweet, salty, and sour tastes, and they desire increased seasonings. These taste changes are caused by the cancer and the various modes of therapy.

In cancer, cachexia occurs, despite efforts to nourish the client, because of the tumor's effects on the client's metabolism in which increased resting energy expenditure can occur despite the reduced dietary intake, indicating a malfunction of metabolism that rarely can be explained by the actual energy demands of the tumor. Several substances produced by the tumor have been identified as mediators of tissue wasting in cachexia. A lipid- mobilizing factor stimulates lipolysis and increases energy expenditure. Cachexia-inducing tumors also produce a chemical that causes protein catabolism in skeletal muscle, while visceral protein is preserved. Of particular relevance to nutrition is that a polyunsaturated fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), weakens the activity of this proteolytic-inducing factor and prevents loss of skeletal muscle.

ASSESSMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Cancer also changes the client's carbohydrate metabolism. Insulin resistance is common. The client can no longer produce glucose efficiently from carbohydrate but instead uses tissue protein for energy. In traumatized non-cancer clients, catabolism of fat for fuel gradually replaces protein breakdown, but the cancer client's body does not make this adaptive change. Another likely causative factor in cachexia is the body's inflammatory response to the tumor. Treatment with anti-

inflammatory drugs seems to have an anabolic effect.

Unexplained weight loss is one of the seven danger signals of cancer, but it is not a universal sign. Compared to 80 percent of clients with cancers of the stomach and pancreas who experienced weight loss, just 31 to 40 percent of those with breast or hematologic cancers or sarcomas and 54 to 64 percent of those with cancers of the colon, lung, and prostate were so affected. Anorexia and changes in the sense of taste often precede the diagnosis of cancer. Because the tumor alters the person's metabolism, it is possible for weight loss to occur without a reduction in food intake. Involuntary weight loss of more than 10 percent is associated with poorer survival rates, and percentage of weight loss is a sensitive and specific tool that can effectively screen and identify malnutrition in cancer clients. In addition, compared to 10 percent of those remaining disease free, unexplained weight loss occurred in 84 percent of breast cancer clients who developed recurrences, and the weight loss preceded the diagnosis of recurrence by 4 to 12 months. As cancer clients often develop ascites as well as other third-space sequestering of fluids, interpreting the weight gain or loss may be difficult. Nevertheless, weight is an important measure of progress in treating ascites.

Serum proteins, particularly albumin, reflect skeletal muscle and visceral protein status. Increased breakdown of the body's tissues and catabolism of the albumin produces low serum albumin levels. Hypoalbuminemia also may be caused by nephrotic syndrome or loss of proteins from removal of third-space fluids. Serum transferrin is also used as a marker for protein status. Because its half-life is 8 days, compared with 20 days for albumin, serum transferrin levels reflect the client's responses to stress or to nutritional support faster than serum albumin levels.

Some nutritional problems in cancer clients are due to the disease, and others are due to treatment modalities. Common problems affecting the consumption of meals and nourishment of cancer clients are early satiety and anorexia, taste alterations, local effects in the mouth, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, and altered immune response.

Early Satiety and Anorexia

Although they may look starved, cancer clients may take a few bites of food and declare that they are full. They may say that they have no appetite at all. The main source of this symptom is the cancer itself, by mechanisms that are beginning to be understood. Control of the disease improves the appetite. Sometimes, though, the physical pressure from the tumor or third-space fluid accumulation may give a feeling of fullness. Relieving that problem may improve food intake.

Some additional factors may interfere with appetite. The psychological stress of dealing with cancer may produce anxiety or depression. The person may be grappling with a body image change or may be going through the grieving process for the loss of a body function or the potential loss of life itself.

Taste Alterations

Cancer patients often have changes in taste perceptions, particularly a decreased threshold for bitterness. Accordingly, they will often say that beef and pork taste bitter or metallic. Some clients report a decreased sensation of sweet, salty, and sour tastes, and they desire increased seasonings. These taste changes are caused by the cancer and the various modes of therapy.

Local Effects in the Mouth

Patients who are being treated with radiation for head and neck cancers often experience mouth ulcers, decreased

and thick saliva, and swallowing difficulty. Any of these may interfere with nutritional intake.

Nausea, vomiting, and Diarrhea

This triad of symptoms often accompanies radiation treatment or chemotherapy, as well as certain types of tumors. Since the gastrointestinal tract cells normally are replaced every few days, these rapidly dividing cells are more vulnerable to the cancer treatments than are more slowly reproducing body cells. Not all clients suffer these side effects to the same extent, and they generally cease when the treatment is completed.

Radiation enteritis involves injury to the intestine. Patients at greater risk of radiation enteritis are those who are thin; who have had previous abdominal surgery; who have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or pelvic inflammatory disease; or who receive chemotherapy along with the radiation. Delays in onset of symptoms of 20 years have been reported. A case was reported of a client whose anal ulcer caused by radiotherapy was healed in 7 weeks with oral vitamin A.

Patients who are being treated with radiation for head and neck cancers often experience mouth ulcers, decreased

and thick saliva, and swallowing difficulty. Any of these may interfere with nutritional intake.

Nausea, vomiting, and Diarrhea

This triad of symptoms often accompanies radiation treatment or chemotherapy, as well as certain types of tumors. Since the gastrointestinal tract cells normally are replaced every few days, these rapidly dividing cells are more vulnerable to the cancer treatments than are more slowly reproducing body cells. Not all clients suffer these side effects to the same extent, and they generally cease when the treatment is completed.

Radiation enteritis involves injury to the intestine. Patients at greater risk of radiation enteritis are those who are thin; who have had previous abdominal surgery; who have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or pelvic inflammatory disease; or who receive chemotherapy along with the radiation. Delays in onset of symptoms of 20 years have been reported. A case was reported of a client whose anal ulcer caused by radiotherapy was healed in 7 weeks with oral vitamin A.

Altered Immune Response

Sometimes, antineoplastic agents also suppress the patient's immune system. Clients receiving them are at risk of overwhelming infections from organisms that would not affect other persons. Clients receiving radiation therapy or radiation as part of bone marrow transplantation also are at high risk of infections and need to be protected from all organisms, even those that are harmless to most healthy people.

NUTRITIONAL INTERVENTION

Based on the problem areas just listed, dietary alterations are suggested. .

For Early Satiety and Anorexia

Many nutrient-dense feedings are offered to the cancer client. For instance, adding 1 1/3 cups of instant dry skim milk powder to 1 quart of liquid milk increases the nutrient density, with little or no change in palatability. Similarly, 1 tablespoon of dry skim milk powder can be added to foods such as mashed potatoes and puddings. Cancer patients should be encouraged to eat whether they are hungry or not. Appropriate exercise before meals may help to stimulate appetite. Attractively prepared food served in a pleasant environment is enticing. Very small servings, offered frequently, may increase the patient's intake. For clients in the hospital or hospice, receiving favorite foods from home or sharing a meal with the family may help overcome the client's aversion to food and offer the family the opportunity to contribute to a loved one's care. Unfortunately the case was not proved in one study that found neither calorie nor protein intake differed significantly between two groups of pediatric oncology clients eating with their caregivers versus alone, but satisfaction with food service was significantly higher in the social dining group (Williams et al, 2004). Children sometimes can be coaxed to eat by decorating their food with faces or serving it in the form of designs such as cars or dolls or the child's name. Involving the child in food preparation or in choosing the menu can help to stimulate the appetite.

Sometimes, antineoplastic agents also suppress the patient's immune system. Clients receiving them are at risk of overwhelming infections from organisms that would not affect other persons. Clients receiving radiation therapy or radiation as part of bone marrow transplantation also are at high risk of infections and need to be protected from all organisms, even those that are harmless to most healthy people.

NUTRITIONAL INTERVENTION

Based on the problem areas just listed, dietary alterations are suggested. .

For Early Satiety and Anorexia

Many nutrient-dense feedings are offered to the cancer client. For instance, adding 1 1/3 cups of instant dry skim milk powder to 1 quart of liquid milk increases the nutrient density, with little or no change in palatability. Similarly, 1 tablespoon of dry skim milk powder can be added to foods such as mashed potatoes and puddings. Cancer patients should be encouraged to eat whether they are hungry or not. Appropriate exercise before meals may help to stimulate appetite. Attractively prepared food served in a pleasant environment is enticing. Very small servings, offered frequently, may increase the patient's intake. For clients in the hospital or hospice, receiving favorite foods from home or sharing a meal with the family may help overcome the client's aversion to food and offer the family the opportunity to contribute to a loved one's care. Unfortunately the case was not proved in one study that found neither calorie nor protein intake differed significantly between two groups of pediatric oncology clients eating with their caregivers versus alone, but satisfaction with food service was significantly higher in the social dining group (Williams et al, 2004). Children sometimes can be coaxed to eat by decorating their food with faces or serving it in the form of designs such as cars or dolls or the child's name. Involving the child in food preparation or in choosing the menu can help to stimulate the appetite.

To Combat Bitter or Metallic Tastes

Oral hygiene before meals freshens the mouth. Sometimes lemon-flavored beverages improve taste sensations. As protein sources, eggs, fish, poultry, beef, pork and dairy products are not good option. Sweet sauces and marinades added to food may improve its palatability.

For Local Effects About the Mouth

A single canker sore can be remarkably painful. A cancer patient with multiple oral ulcerations may complain of severe pain on food ingestion. In addition, some patients also have a dry mouth and difficulty swallowing. For all of these problems, good oral hygiene, before and after meals, is essential.

MOUTH ULCERATIONS

Foods should be soft and mild. Sauces, gravies, and dressings may make foods easier to eat. Cream soups and plant-based milk provide much nutrition for the volume ingested. Cold foods have a somewhat numbing effect and may be better tolerated than hot food. Taking liquids with meals helps wash down the food. Drinking straws may help get the liquids past mouth ulcerations. Substances likely to irritate the mouth ulcerations should be avoided. These may include hot items, salty or spicy foods, acidic juices, and alcohol (even in mouthwash).

Oral hygiene before meals freshens the mouth. Sometimes lemon-flavored beverages improve taste sensations. As protein sources, eggs, fish, poultry, beef, pork and dairy products are not good option. Sweet sauces and marinades added to food may improve its palatability.

For Local Effects About the Mouth

A single canker sore can be remarkably painful. A cancer patient with multiple oral ulcerations may complain of severe pain on food ingestion. In addition, some patients also have a dry mouth and difficulty swallowing. For all of these problems, good oral hygiene, before and after meals, is essential.

MOUTH ULCERATIONS

Foods should be soft and mild. Sauces, gravies, and dressings may make foods easier to eat. Cream soups and plant-based milk provide much nutrition for the volume ingested. Cold foods have a somewhat numbing effect and may be better tolerated than hot food. Taking liquids with meals helps wash down the food. Drinking straws may help get the liquids past mouth ulcerations. Substances likely to irritate the mouth ulcerations should be avoided. These may include hot items, salty or spicy foods, acidic juices, and alcohol (even in mouthwash).

DRY MOUTH

Adequate hydration helps keep the mouth moist. Food lubricants can be of value.

SWALLOWING DIFFICULTY

This problem may linger throughout a course of treatment. To combat it, clients should make swallowing a conscious act. They should inhale, swallow, and exhale. They should experiment with head position. Tilting the head backward or forward may help. Foods for these clients should be non sticky and of even consistency. Lumpy gravy and mixed vegetables, for example, are hard to manage.

Adequate hydration helps keep the mouth moist. Food lubricants can be of value.

SWALLOWING DIFFICULTY

This problem may linger throughout a course of treatment. To combat it, clients should make swallowing a conscious act. They should inhale, swallow, and exhale. They should experiment with head position. Tilting the head backward or forward may help. Foods for these clients should be non sticky and of even consistency. Lumpy gravy and mixed vegetables, for example, are hard to manage.

For Nausea, Vomiting, and Diarrhea

Antiemetic medications should be given an appropriate number of hours before chemotherapy begins and continued on a regular schedule. These drugs are most effective if given prophylactically before the client becomes nauseated. Identifying the pathway inducing nausea and vomiting helps to select effective medications, which might include a derivative of marijuana, dronabinol. Similarly, medications for pain and insomnia must be given liberally, but an opioid regimen also necessitates measures to prevent constipation. Because nausea and vomiting frequently accompany pain in patients without cancer, so, too, controlling the cancer patient's pain may alleviate nausea.

As with morning sickness, eating dry crackers before arising may alleviate the nausea. Liquids taken between meals, rather than with them, reduce the volume in the stomach. Similarly, a low-fat diet is digested faster, leaving less content in the stomach to cause nausea or to be vomited. Patients should eat slowly and chew thoroughly. Resting after eating and taking liquids 30 to 60 minutes after solid food helps to control nausea. Foods the patient especially likes should be saved for times when the client feels well, so that these favorite foods do not become associated with vomiting and are thereafter avoided. Food aversions develop in more than half of chemotherapy patients, usually involving two to four foods, but they may be accepted several weeks or months after the completion of therapy.

Antiemetic medications should be given an appropriate number of hours before chemotherapy begins and continued on a regular schedule. These drugs are most effective if given prophylactically before the client becomes nauseated. Identifying the pathway inducing nausea and vomiting helps to select effective medications, which might include a derivative of marijuana, dronabinol. Similarly, medications for pain and insomnia must be given liberally, but an opioid regimen also necessitates measures to prevent constipation. Because nausea and vomiting frequently accompany pain in patients without cancer, so, too, controlling the cancer patient's pain may alleviate nausea.

As with morning sickness, eating dry crackers before arising may alleviate the nausea. Liquids taken between meals, rather than with them, reduce the volume in the stomach. Similarly, a low-fat diet is digested faster, leaving less content in the stomach to cause nausea or to be vomited. Patients should eat slowly and chew thoroughly. Resting after eating and taking liquids 30 to 60 minutes after solid food helps to control nausea. Foods the patient especially likes should be saved for times when the client feels well, so that these favorite foods do not become associated with vomiting and are thereafter avoided. Food aversions develop in more than half of chemotherapy patients, usually involving two to four foods, but they may be accepted several weeks or months after the completion of therapy.

Avoid strong cooking odors by selecting milder foods, ventilating the kitchen. As with the patient who has gastrointestinal upset, clear liquids should be tried first, after vomiting ceases, and the diet progressed as tolerated. Unconventional mealtimes may be instituted to ensure that the client receives nourishment when nausea is minimal. If this means that breakfast is eaten at 2 AM and lunch at 6 AM, so be it. This accommodation is truly individualized care.

Maintenance of fluid and electrolyte intake is critical in the client with diarrhea, and early recognition and treatment can modify this complication. Among the dietary modifications that may be used are the following:

For Altered Immune Response

Patients may be placed in protective isolation to minimize their exposure to microorganisms. As for dietary interventions, fresh fruits and fresh vegetables should be washed adequately.

Maintenance of fluid and electrolyte intake is critical in the client with diarrhea, and early recognition and treatment can modify this complication. Among the dietary modifications that may be used are the following:

- Adding pectin-containing foods to the client's intake

- Implementing a low-residue diet

- Testing for and treating lactose intolerance

- Restoring intestinal bacteria with probiotics

For Altered Immune Response

Patients may be placed in protective isolation to minimize their exposure to microorganisms. As for dietary interventions, fresh fruits and fresh vegetables should be washed adequately.

Submit Unit Task Here

Create a Reflective Journal on your learning in this unit including your thoughts on the existing controversy between dietary guidelines and nutritional therapy evidences for cancer patients.