Culinary Skills 1 - Unit 2

UNIT 2 |

GOALS:

OBJECTIVES:

REFERENCES:

- Appreciate the numerous benefits of a Whole Food Plant-based Diet

- Implement efficient strategies for Shifting Diets

- Realize the advantage of Eating Mindfully to address certain chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity

- Utilize certain ingredients that can be added in cooking WFPB recipes

OBJECTIVES:

- Identify evidence-based benefits of Whole Food Plant-based Diet for improving health outcome

- Describe Protein Flip and Dessert Flip during the diet transition

- Describe the benefits of Mindful eating for chronic disease

- Identify the effects of certain ingredients added to WFPB preparations

- Discuss the common Misconceptions about WFPB Diet

REFERENCES:

- American College of Lifestyle Medicine, Michelle Hauser, MD

- Nutrition Guide for Clinicians, Neal Barnard, MD

- Proteinaholic, Garth Davis, MD

The more whole, plant foods and fewer highly processed, calorie-dense, and animal-derived foods one eats, the more health benefits one accumulates (e.g., reduced risk of chronic diet-related diseases, increased longevity, etc.) and the less time one needs to spend worrying about such activities as counting calories or restricting portion sizes to maintain or lose weight. Plant foods are also filled with fiber and antioxidants.

Benefits of Whole Food Plant-Based Diet

- Decreases in all-cause mortality

- Weight loss and favorable changes in lipid profile

- Decreased risk, and even reversal, of cardiovascular disease

- Decreased risk of some cancers

- Reduced markers of early stage, biopsy-proven, prostate cancer

- Decreased risk of diabetes and improved glycemic control or normalized blood glucose levels for those with diabetes

- Improved migraine symptoms

It is important to note that many studies showing the benefits of diets high in whole, plant foods are not studying purely WFPB diets. Many (if not most) refer to predominantly WFPB, vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian, or Mediterranean-style diets.

Predominantly WFPB diet: The diet promoted by CulinaryMD is a dietary pattern centered on whole, plant foods, including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Processed foods and animal foods are limited or excluded.

Entirely WFPB diet: A dietary pattern made up entirely of whole, plant foods, including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. It completely excludes meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, dairy, eggs, oil, refined sugars, and refined grains.

Vegan diet (otherwise known as a strict vegetarian diet): This diet includes no animal products (i.e., no meat, poultry, seafood, dairy products, or eggs) but could include any plant-based foods. A vegan diet does not necessarily limit unhealthy processed foods if they are free of animal products. However, most following vegan diets eat healthier than the general public, primarily owing to a higher intake of plant foods. A purely WFPB diet is a low-fat, vegan diet based on whole foods. A predominantly WFPB diet is not vegan if it includes animal-derived foods.

Vegetarian diet (otherwise known as a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet): This diet is similar to a vegan diet but includes dairy products and eggs. A vegetarian diet does not necessarily limit unhealthy processed foods provided they are free of animal products requiring an animal to be killed to obtain the food (e.g., meat, poultry, seafood, gelatin, etc.). However, most following vegetarian diets eat healthier than the general public, primarily owing to a higher intake of plant foods.

Pescatarian diet: This is similar to either a vegan or vegetarian diet but with the addition of fish and/or seafood. Pescatarians do not eat meat or poultry.

Mediterranean-style diet: It is a predominantly (but not entirely) plant-based diet with staples including whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, seeds, and plant oils, such as olive oil. Fish and seafood are eaten 2-3 times weekly, along with small amounts of dairy, eggs, and poultry. Wine in moderation is also included. Red meat, processed meat, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars are generally avoided. (*There are a variety of Mediterranean diets. This description refers to the type of Mediterranean diet most commonly described in clinical trials, which has been the topic of numerous health-related studies and dietary guidelines. Actual foods eaten do not need to be those found in the Mediterranean region of the world.)

Entirely WFPB diet: A dietary pattern made up entirely of whole, plant foods, including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. It completely excludes meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, dairy, eggs, oil, refined sugars, and refined grains.

Vegan diet (otherwise known as a strict vegetarian diet): This diet includes no animal products (i.e., no meat, poultry, seafood, dairy products, or eggs) but could include any plant-based foods. A vegan diet does not necessarily limit unhealthy processed foods if they are free of animal products. However, most following vegan diets eat healthier than the general public, primarily owing to a higher intake of plant foods. A purely WFPB diet is a low-fat, vegan diet based on whole foods. A predominantly WFPB diet is not vegan if it includes animal-derived foods.

Vegetarian diet (otherwise known as a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet): This diet is similar to a vegan diet but includes dairy products and eggs. A vegetarian diet does not necessarily limit unhealthy processed foods provided they are free of animal products requiring an animal to be killed to obtain the food (e.g., meat, poultry, seafood, gelatin, etc.). However, most following vegetarian diets eat healthier than the general public, primarily owing to a higher intake of plant foods.

Pescatarian diet: This is similar to either a vegan or vegetarian diet but with the addition of fish and/or seafood. Pescatarians do not eat meat or poultry.

Mediterranean-style diet: It is a predominantly (but not entirely) plant-based diet with staples including whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, seeds, and plant oils, such as olive oil. Fish and seafood are eaten 2-3 times weekly, along with small amounts of dairy, eggs, and poultry. Wine in moderation is also included. Red meat, processed meat, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars are generally avoided. (*There are a variety of Mediterranean diets. This description refers to the type of Mediterranean diet most commonly described in clinical trials, which has been the topic of numerous health-related studies and dietary guidelines. Actual foods eaten do not need to be those found in the Mediterranean region of the world.)

Shifting Diets

Protein Flip

This term was popularized by the Culinary Institute of America, one of the premier culinary schools in the U.S. It is the practice of flipping the plate from meat-centric to plant-centric. Instead of meat making up the center of the plate, with vegetables being the smaller portion or an afterthought, vegetables, and other plants become the stars while meat portions get reduced to garnishes or sides. This is a great strategy for patients who are not willing to give up meat entirely but could benefit from reducing intake and/or substituting it with plant sources of protein. In a typical meal, one might have eaten a large piece of chicken with a small side salad. In a Protein Flip, the portions are reversed. In a Protein Flip, this meal may become a large salad with added whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds to make the salad more filling and increase the protein content while reducing the portion of chicken to 1-2 ounces sliced atop the salad as a garnish.

The Protein Flip can be the gateway to healthier foods. This technique is very useful for those who are uninterested or unwilling to cut unhealthy foods-such as red meat-out of their diets completely. It also adds the familiarity of something they associate with deliciousness and satiety (e.g., meat) to foods previously eschewed from the diet (e.g., vegetables). Finding a way to incorporate these healthier foods into the diet helps one to develop a taste for them, making it more likely they will try other vegetables or choose them as a regular part of their diet.

When making dietary shifts-even if interested in cutting down or cutting out meat and other animal products-cravings for these items can remain intense for quite some time. This makes sense since food is part of culture, memories, and time shared with loved ones. The Protein Flip method of incorporating small amounts of highly craved foods may help some people prevent binging on them after periods of trying to abstain completely. Satisfying a craving can also help some people limit total food consumed because their psychological hunger (a desire to eat for a variety of reasons such as a habit, emotional state, or because something looks or tastes good separate from physiologic hunger) is quenched. For others, however, controlling portions of these foods is challenging, and they may find it easier to eliminate them completely.

Dessert Flip

Trying to reduce the amount of very sweet foods-including artificially sweetened foods eaten is important for retraining

the palette to appreciate the natural sweetness in healthier options, such as fruit. In a typical dessert, one might have a large piece of a decadent sweet garnished with a bit of fruit—think strawberry cheesecake with a sliced strawberry on top. In a Dessert Flip, the portions are reversed. The size of the decadent dessert is reduced to just a bite or two and accompanied by a larger arrangement of fresh fruit. This is generally just as satisfying as the original while increasing the nutrient density and decreasing the calorie density. This is because the most enjoyable bites of any dessert are the first, and having a couple of bites is generally enough to quench a sweet craving at the end of a meal. The Dessert Flip is not the same as a healthy dessert, which is nutritious in its own right.

While the Dessert Flip, like the Protein Flip, works well for some to satiate cravings and prevent binging on sugary foods, other individuals may struggle to limit highly palatable foods to a few bites and may prefer to cut added sugars altogether. Work with your patients to find out what works best for them. Both approaches achieve the overall goal of reducing added sugars in the diet.

This term was popularized by the Culinary Institute of America, one of the premier culinary schools in the U.S. It is the practice of flipping the plate from meat-centric to plant-centric. Instead of meat making up the center of the plate, with vegetables being the smaller portion or an afterthought, vegetables, and other plants become the stars while meat portions get reduced to garnishes or sides. This is a great strategy for patients who are not willing to give up meat entirely but could benefit from reducing intake and/or substituting it with plant sources of protein. In a typical meal, one might have eaten a large piece of chicken with a small side salad. In a Protein Flip, the portions are reversed. In a Protein Flip, this meal may become a large salad with added whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds to make the salad more filling and increase the protein content while reducing the portion of chicken to 1-2 ounces sliced atop the salad as a garnish.

The Protein Flip can be the gateway to healthier foods. This technique is very useful for those who are uninterested or unwilling to cut unhealthy foods-such as red meat-out of their diets completely. It also adds the familiarity of something they associate with deliciousness and satiety (e.g., meat) to foods previously eschewed from the diet (e.g., vegetables). Finding a way to incorporate these healthier foods into the diet helps one to develop a taste for them, making it more likely they will try other vegetables or choose them as a regular part of their diet.

When making dietary shifts-even if interested in cutting down or cutting out meat and other animal products-cravings for these items can remain intense for quite some time. This makes sense since food is part of culture, memories, and time shared with loved ones. The Protein Flip method of incorporating small amounts of highly craved foods may help some people prevent binging on them after periods of trying to abstain completely. Satisfying a craving can also help some people limit total food consumed because their psychological hunger (a desire to eat for a variety of reasons such as a habit, emotional state, or because something looks or tastes good separate from physiologic hunger) is quenched. For others, however, controlling portions of these foods is challenging, and they may find it easier to eliminate them completely.

Dessert Flip

Trying to reduce the amount of very sweet foods-including artificially sweetened foods eaten is important for retraining

the palette to appreciate the natural sweetness in healthier options, such as fruit. In a typical dessert, one might have a large piece of a decadent sweet garnished with a bit of fruit—think strawberry cheesecake with a sliced strawberry on top. In a Dessert Flip, the portions are reversed. The size of the decadent dessert is reduced to just a bite or two and accompanied by a larger arrangement of fresh fruit. This is generally just as satisfying as the original while increasing the nutrient density and decreasing the calorie density. This is because the most enjoyable bites of any dessert are the first, and having a couple of bites is generally enough to quench a sweet craving at the end of a meal. The Dessert Flip is not the same as a healthy dessert, which is nutritious in its own right.

While the Dessert Flip, like the Protein Flip, works well for some to satiate cravings and prevent binging on sugary foods, other individuals may struggle to limit highly palatable foods to a few bites and may prefer to cut added sugars altogether. Work with your patients to find out what works best for them. Both approaches achieve the overall goal of reducing added sugars in the diet.

Healthy and Delicious Meals

This course teaches how to make healthy dishes delicious and craveable. Humans are wired to seek out delicious food, healthy or not. The best ways to get people to eat more healthy foods and fewer unhealthy foods are to make the formertaste as good (or better!) and be as accessible as the latter.

Recipes

When cooking, there is no award for following a recipe to the letter. Many recipes available on the Internet have yet to be tested. If a recipe from a source of unknown reputation fails, you have no idea if it's you, the ingredients, or the recipe. Learn to trust your gut. If you feel that a dish is better with a tweak or addition, try it. Recipes are included throughout the course since some people like to follow recipes, while others just like to have a general guide on their cooking journey. Recipes also help you to shop for appropriate amounts and types of ingredients for each session.

Recipes

When cooking, there is no award for following a recipe to the letter. Many recipes available on the Internet have yet to be tested. If a recipe from a source of unknown reputation fails, you have no idea if it's you, the ingredients, or the recipe. Learn to trust your gut. If you feel that a dish is better with a tweak or addition, try it. Recipes are included throughout the course since some people like to follow recipes, while others just like to have a general guide on their cooking journey. Recipes also help you to shop for appropriate amounts and types of ingredients for each session.

Balancing Flavors & Textures

Good cooking begins with tasting and learning to adjust flavors. Begin to taste foods for sweet, salty, bitter, acidic, and umami (savory) flavors. Note whether a flavor predominates or if flavors are balanced. Think about what you ideally want regarding flavor from a final dish. Do you want something with an acidic tang, or do you prefer a savory, balanced dish? If the flavors of the dish are not where you want them to be, try to balance them using flavoring ingredients with other aspects of taste. For example, if a food is too acidic or bitter, try adding something sweet. If a dish is bland, try adding a few drops of acid, such as lemon juice, vinegar, or hot sauce, and then salt to taste (if using salt). From a culinary perspective, when salting, the optimal level of flavor (without over-salting) is achieved when you can taste the flavor of the food toward the back of your tongue but don't get a dry or parched feeling in your throat after eating it. From a medical perspective, to reduce salt intake, consider adding herbs or spices to savory foods or cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, or ginger to sweet foods to limit the amount of salt that you need to make the dish delicious. Adding a little acid to a dish prior to salting also heightens flavor and can reduce the amount of salt needed.

The texture is also an important consideration. Crisp and crunchy textures stimulate the appetite; this is why most appetizers have a crisp component. Creamy textures can be comforting, but anyone required to eat a pureed diet for any length of time will tell you how boring and unappetizing meals are when every item has the same texture. The best meals incorporate a variety of textures. Textures can have positive and negative associations for some eaters. If someone is averse to a certain food, make sure to explore whether the flavor, texture, or both are issues. Oftentimes, someone may be averse to a vegetable cooked in a way that gives it a certain texture but enjoy it prepared another way.

Good cooking begins with tasting and learning to adjust flavors. Begin to taste foods for sweet, salty, bitter, acidic, and umami (savory) flavors. Note whether a flavor predominates or if flavors are balanced. Think about what you ideally want regarding flavor from a final dish. Do you want something with an acidic tang, or do you prefer a savory, balanced dish? If the flavors of the dish are not where you want them to be, try to balance them using flavoring ingredients with other aspects of taste. For example, if a food is too acidic or bitter, try adding something sweet. If a dish is bland, try adding a few drops of acid, such as lemon juice, vinegar, or hot sauce, and then salt to taste (if using salt). From a culinary perspective, when salting, the optimal level of flavor (without over-salting) is achieved when you can taste the flavor of the food toward the back of your tongue but don't get a dry or parched feeling in your throat after eating it. From a medical perspective, to reduce salt intake, consider adding herbs or spices to savory foods or cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, or ginger to sweet foods to limit the amount of salt that you need to make the dish delicious. Adding a little acid to a dish prior to salting also heightens flavor and can reduce the amount of salt needed.

The texture is also an important consideration. Crisp and crunchy textures stimulate the appetite; this is why most appetizers have a crisp component. Creamy textures can be comforting, but anyone required to eat a pureed diet for any length of time will tell you how boring and unappetizing meals are when every item has the same texture. The best meals incorporate a variety of textures. Textures can have positive and negative associations for some eaters. If someone is averse to a certain food, make sure to explore whether the flavor, texture, or both are issues. Oftentimes, someone may be averse to a vegetable cooked in a way that gives it a certain texture but enjoy it prepared another way.

Ingredients Added for WFPB Diets

You may note the occasional use of small amounts of optional sugar, salt, and oil throughout the recipes and lessons. These items are used solely to bring out and balance the flavors of otherwise whole and plant-based foods. They are not used as main ingredients or in large amounts, so the whole of the curriculum is still reflective of a predominantly WFPB diet. The vast majority of the added sugars, oil, and salt in people's diets come from processed and prepared foods.

Transitioning to cooking as much of your own food as possible is the best way to reduce these items in the diet. Even if you add a pinch of salt or sugar to a dish to balance flavors, you will be eating a tiny fraction of what you would have eaten had you chosen to order off the menu at a nearby restaurant. In most instances, alternatives or modifications of cooking methods are given to limit or eliminate these items. Therefore, if you wish to eliminate any use of these items strictly, you should also do so and omit recipes.

Transitioning to cooking as much of your own food as possible is the best way to reduce these items in the diet. Even if you add a pinch of salt or sugar to a dish to balance flavors, you will be eating a tiny fraction of what you would have eaten had you chosen to order off the menu at a nearby restaurant. In most instances, alternatives or modifications of cooking methods are given to limit or eliminate these items. Therefore, if you wish to eliminate any use of these items strictly, you should also do so and omit recipes.

|

Sugar

In most foods that are high in added sugars, the purposes of the sugars are to preserve, make hyper-palatable, and add flavor to foods otherwise stripped of naturally complex flavors through ultra-processing. Sugars are not used for these purposes in this curriculum. Sugars used in this curriculum balance flavors, as sugars occur naturally to varying degrees in most foods, particularly by ripeness and season. Consider eating a store-bought, under-ripe tomato and recall its slightly sour taste. Contrast that with a sun-ripened tomato from the garden, dripping with juicy sweetness at each bite. There are many more naturally occurring sugars than in the former. |

A pinch of sugar, for example, can help balance the sourness of under-ripe tomatoes in a dish so that the result tastes similarly sweet as the dish with the ripe tomato. When adding very small amounts of sugar to food, it matters little to health which type (e.g., white, brown, raw, honey, date paste, etc.) you use as most have similar physiological effects. However, in larger quantities, sweeteners have different cooking properties from one another and, therefore, cannot be used interchangeably without altering other parts of the recipe. Details of how to convert between different types of sweeteners in recipes using large amounts of added sugars are beyond the scope of this curriculum. For those who wish to use minimally refined or wholly natural sugars, you may want to opt for dates, date paste, honey, or maple syrup. Nearly all recipes in the curriculum that call for sweeteners give these options. To make date paste, simply remove the pits from the dates and puree them in a food processor with just enough boiling water to allow the dates to transform into a smooth paste. You can store extra date paste in the freezer. The high sugar content makes the mixture scoopable when frozen, so you can take it out a little to use here and there as needed.

|

Oil

Throughout the curriculum, oil is optional and limited, and its use. Instructions for recipes containing optional oil are given on modifying cooking methods to achieve the best results if the oil is omitted. For those whose main dietary goal is the prevention of chronic disease, there is good evidence for a Mediterranean-style diet promoting health; this diet includes liquid plant oils. For those aiming to reverse the cardiovascular disease or early-stage prostate cancer, there is more support for an oil-free (or nearly oil-free) WFPB diet. Oil is limited or excluded from a predominantly WFPB diet because it is not a whole food. |

Oil is pressed or extracted from whole foods (such as olives, avocados, nuts, and seeds) to remove beneficial components, including fiber, water, and micronutrients. The resulting oil is calorie-dense and nutrient-poor compared with the original whole food from which it was derived. While this curriculum focuses on a predominantly WFPB diet, optional oil is included in recipes and lessons because people have a spectrum of health goals, come from different food cultures, and may be at various stages of change with regard to their diet. In cooking, oil facilitates the browning and crisping of foods, which imbues complex flavor characteristics. It prevents sticking and allows one to cook vegetables quickly over high heat in ways that maintain their bright colors and crisp textures. For many, it is part of making food irresistibly delicious and can be a gateway ingredient to facilitate getting more vegetables, whole grains, and legumes onto the plates of those who have been reluctant to eat them in the past.

For a medical professional taking a Culinary Medicine course, it may be useful to learn to cook both with and without oil so that you can tailor motivational interviewing around dietary behavior changes to a given patient's needs and preferences.

For a medical professional taking a Culinary Medicine course, it may be useful to learn to cook both with and without oil so that you can tailor motivational interviewing around dietary behavior changes to a given patient's needs and preferences.

|

Salt

Salt, which contains sodium, is not specifically restricted in a WFPB diet, but the literature shows that too much sodium intake can be detrimental to the health of those sensitive to it. Evidence-based diets focused on lowering sodium and saturated fat, and increasing plant foods, such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, have been shown to reduce blood pressure, heart attacks, and strokes. More than 70% of the sodium people get in their diets is from processed and prepared foods, while only about 5% comes from salt added while cooking, and another 5% from salting at the table. |

From a culinary perspective, salt is included in the curriculum because it helps transfer the flavors in foods to your taste buds. If one were to make all of their food at home with whole foods and salt to taste, they would likely consume only a small fraction of the sodium eaten by someone who consumes many processed and prepared foods. That said, most dishes in the curriculum do utilize a variety of ingredients (e.g., spices, herbs, acidic ingredients) and cooking techniques that increase the flavor in order to reduce the reliance on salt to enhance flavor. If you want to avoid all added salt, make sure to increase the other flavoring ingredients in the dish and/or consider adding a squeeze of lemon or some additional herbs and spices to bolster flavor. There are many salt-free dried herbs, spice, and vegetable blends available commercially for this purpose.

Common Misconceptions on WFPB Diet

Where do you get your____________. This question needs no explanation for anyone who has followed WFPB, vegetarian, or vegan diets at any point in their lives. Growing up in a society in which we're taught to drink milk to build strong bones, and a big hunk of meat is generally the center of the dinner plate, well-meaning family members and friends worry about the health of those that forego these items. However, the literature clearly shows well-planned vegan and vegetarian diets provide all necessary nutrients. According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, "vegetarian, including total vegetarian or vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases."

The American Association of Pediatrics has also published a detailed manuscript regarding vegan diets in infants, children, and adolescents with details on how to make sure all necessary nutrients are included in sufficient amounts. A balanced, calorically appropriate diet based on a variety of whole foods, including vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, is also generally sufficient in macronutrients and micronutrients. In fact, it is easier to be sufficient in most of the nutrients of concern when following a WFPB diet than most typical diets. Notable exceptions are Vitamins B12 and D, which are common deficiencies among those eating nearly any type of diet. Selected details follow about nutrition questions likely to arise in courses or conversations promoting WFPB diets.

Where do you get your Calcium?

Calcium is a key mineral involved in human health and is best known for its role in promoting bone health. The daily recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for calcium from the Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies ranges from 1,000 mg to 1,300 mg, depending on age, for those aged four years and older. For many, calcium is thought to be synonymous with dairy, and to eschew dairy is to be deficient in calcium intake-not true! Taking a moment to think about milk intake, it makes sense that adults would not need dairy. Mammals, including humans, wean well before adulthood.

Calcium is a key mineral involved in human health and is best known for its role in promoting bone health. The daily recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for calcium from the Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies ranges from 1,000 mg to 1,300 mg, depending on age, for those aged four years and older. For many, calcium is thought to be synonymous with dairy, and to eschew dairy is to be deficient in calcium intake-not true! Taking a moment to think about milk intake, it makes sense that adults would not need dairy. Mammals, including humans, wean well before adulthood.

Therefore, it would be a poor design for humans to need lactation products from another mammal (such as dairy milk from cows) to survive, particularly in their adult years. There are plenty of other sources of calcium beyond dairy products in the diet. Plant foods that are good sources of calcium include tofu, tempeh, dark green vegetables, beans, almonds, and fortified plant-based kinds of milk. See the Amounts of Calcium in Dairy and Non-dairy Foods handout for more details. Many people, regardless of dairy consumption, need additional calcium for medical reasons. This can be eaten in the forms of naturally calcium-rich foods and fortified foods or taken as supplemental calcium. Calcium is incorporated into dairy products in a variety of ways, including (1) from the plants that cows eat, (2) calcium supplementation of cow feed, (3) or calcium fortification. Humans can either eat plants or take supplements just as well as cattle. Bonus: avoiding the intake of dairy and beef helps to limit greenhouse gases, deforestation, and other negative environmental impacts.

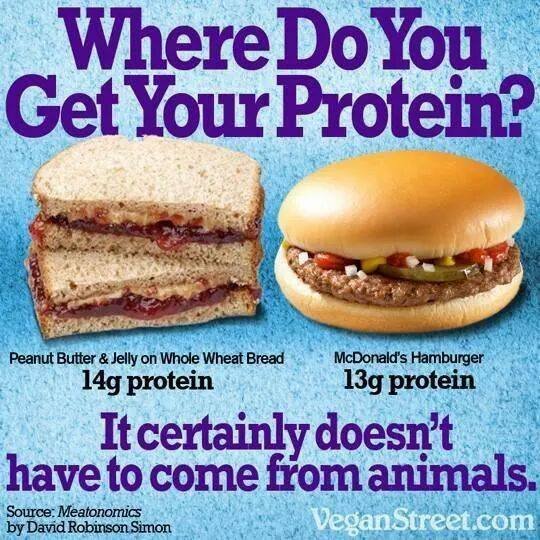

Where do you get your protein?

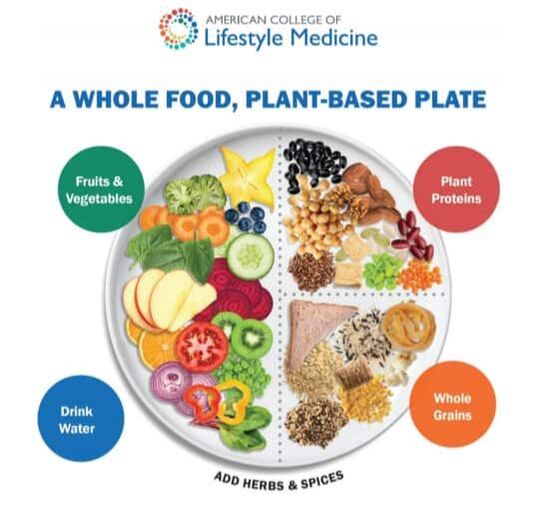

From nearly all the foods that we eat is the answer. Contrary to popular belief, meat does not have a monopoly on protein. Those eating a calorie-sufficient, balanced, plant-based diet will get plenty of protein. Evidence-based food guidelines, such as Canada's Dietary Guidelines, published in January 2019, support moving toward more plant-based diets. Similar to the Canadian Food Guide, The ACLM WFPB Plate highlights WFPB protein options. Note that the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans are influenced by a variety of industry lobbyists and are not wholly evidence-based.

From nearly all the foods that we eat is the answer. Contrary to popular belief, meat does not have a monopoly on protein. Those eating a calorie-sufficient, balanced, plant-based diet will get plenty of protein. Evidence-based food guidelines, such as Canada's Dietary Guidelines, published in January 2019, support moving toward more plant-based diets. Similar to the Canadian Food Guide, The ACLM WFPB Plate highlights WFPB protein options. Note that the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans are influenced by a variety of industry lobbyists and are not wholly evidence-based.

Those not eating plant-based diets generally consume far more protein than is necessary. People in the United States consume more total and animal-based protein per capita than any other country in the world. Although protein is an essential macronutrient, consuming excess protein does not lead to bigger muscles, better health, or improved weight-loss outcomes.

Excess calories from protein or any other macronutrient will be stored as fat. The overconsumption of animal protein, in particular, may be deleterious for the environment as well as one's health. Aim to make plant-based sources of protein a bigger part of the diet. Legumes, beans, tofu, and tempeh are all good plant-based sources of protein. Whole grains and vegetables contain some protein as well. For example, 100 Calories of broccoli contains 8 grams of protein. Recall that in an entirely WFPB diet, plant-based proteins are 100% of proteins consumed. In a predominantly WFPB diet, if including animal

sources of protein, it is still advisable from a health perspective to limit portion sizes and avoid red and processed meats. Of note, poultry and eggs also have the smallest environmental footprint of all animal sources of protein, whereas beef and dairy have the largest.

Excess calories from protein or any other macronutrient will be stored as fat. The overconsumption of animal protein, in particular, may be deleterious for the environment as well as one's health. Aim to make plant-based sources of protein a bigger part of the diet. Legumes, beans, tofu, and tempeh are all good plant-based sources of protein. Whole grains and vegetables contain some protein as well. For example, 100 Calories of broccoli contains 8 grams of protein. Recall that in an entirely WFPB diet, plant-based proteins are 100% of proteins consumed. In a predominantly WFPB diet, if including animal

sources of protein, it is still advisable from a health perspective to limit portion sizes and avoid red and processed meats. Of note, poultry and eggs also have the smallest environmental footprint of all animal sources of protein, whereas beef and dairy have the largest.

Where do you get your OMEGA-3 fatty acids! What about Omega-6 fatty acids?

Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids are essential fatty acids, meaning the body cannot make them endogenously, and they must be consumed from food sources or supplements. Consumption of Omega-3 rich foods is associated with a variety of improved health outcomes. The health effects of consuming plant sources of Omega-3 fatty acids have not been studied as extensively as other sources. However, evidence suggests comparable benefits. Like calcium to dairy, Omega-3 fatty acids are thought to be synonymous with fish since fish is a common source of Omega-3 intake in many diets. However, just as cows don't make calcium, fish do not make Omega-3 fatty acids. Instead, fish concentrate the Omega-3's they ingest from algae and other green, aqueous plants (or the smaller fish they ate that were eating these greens). Humans can get Omega-3's from algal sources as well, but this often isn't palatable in the quantities required. Instead, opt for walnuts, chia seeds, hemp seeds, ground flaxseeds, or take an algal-based Omega-3 supplement if choosing to follow an entirely WFPB diet. For those following a predominantly WFPB diet who choose to incorporate some fish, opt for sustainable and low-mercury, low-contaminant options as mercury and contaminants may counteract some of the benefits of the Omega-3's in fish.

Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids are essential fatty acids, meaning the body cannot make them endogenously, and they must be consumed from food sources or supplements. Consumption of Omega-3 rich foods is associated with a variety of improved health outcomes. The health effects of consuming plant sources of Omega-3 fatty acids have not been studied as extensively as other sources. However, evidence suggests comparable benefits. Like calcium to dairy, Omega-3 fatty acids are thought to be synonymous with fish since fish is a common source of Omega-3 intake in many diets. However, just as cows don't make calcium, fish do not make Omega-3 fatty acids. Instead, fish concentrate the Omega-3's they ingest from algae and other green, aqueous plants (or the smaller fish they ate that were eating these greens). Humans can get Omega-3's from algal sources as well, but this often isn't palatable in the quantities required. Instead, opt for walnuts, chia seeds, hemp seeds, ground flaxseeds, or take an algal-based Omega-3 supplement if choosing to follow an entirely WFPB diet. For those following a predominantly WFPB diet who choose to incorporate some fish, opt for sustainable and low-mercury, low-contaminant options as mercury and contaminants may counteract some of the benefits of the Omega-3's in fish.

|

Omega-6 fatty acids are found in plant oils and are therefore abundant in processed and fast foods. Omega-6 fatty acids are commonly found in such whole foods as nuts and seeds and in smaller amounts in olives and avocados. There is some controversy about the role omega-6 fatty acids play in health. Farvid and colleagues published a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies comparing Omega-6 intake with risk of coronary heart disease that is worth reviewing if time permits.

|

Where do you get your Vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 rich foods include meat, poultry, fish, seafood, dairy products, eggs, and fortified foods, such as breakfast cereals and most plant-based kinds of milk. Much like the Omega-3 fatty acids found in fish, Vitamin B12 is not made by animals but is concentrated in their tissues. Vitamin B12 is only made by bacteria and archaea; it is found in foods only through the interactions of these bacteria and archaea with animals and plants. Those following a WFPB diet can get vitamin B12 from fortified foods (e.g., most plant-based kinds of milk and cereals), nutritional yeast, or nori; otherwise, supplementation is needed. However, most people with Vitamin B12 deficiency are deficient due to non-dietary factors affecting absorption, such as autoimmune diseases, gastrointestinal diseases or surgeries, certain infections, certain drugs, and other causes. Anyone with a medical or dietary cause of Vitamin B12 deficiency needs supplementation.

Vitamin B12 rich foods include meat, poultry, fish, seafood, dairy products, eggs, and fortified foods, such as breakfast cereals and most plant-based kinds of milk. Much like the Omega-3 fatty acids found in fish, Vitamin B12 is not made by animals but is concentrated in their tissues. Vitamin B12 is only made by bacteria and archaea; it is found in foods only through the interactions of these bacteria and archaea with animals and plants. Those following a WFPB diet can get vitamin B12 from fortified foods (e.g., most plant-based kinds of milk and cereals), nutritional yeast, or nori; otherwise, supplementation is needed. However, most people with Vitamin B12 deficiency are deficient due to non-dietary factors affecting absorption, such as autoimmune diseases, gastrointestinal diseases or surgeries, certain infections, certain drugs, and other causes. Anyone with a medical or dietary cause of Vitamin B12 deficiency needs supplementation.

Where do you get your Vitamin D?

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent and has little to do with diet as most Vitamin D (which is actually a hormone and not a vitamin) is made in our skin through a reaction with the sun. For those living more than 37 degrees latitude north or south of the equator, Vitamin D is only made via sun-exposed skin between late spring and early fall, not in the cooler months. Most people who don't make enough Vitamin D need supplementation since few people get enough from diet alone, regardless of the type of diet they eat. In addition to location, the following also increase the risk of vitamin D deficiency: obesity, cancer, darker skin pigmentation, pregnancy, institutionalization, and anyone with limited sun exposure. Dietary sources of vitamin D include fortified foods (dairy and plant-based kinds of milk), oily fish and seafood, egg yolks, mushrooms, animal fat, and liver. For those eating WFPB diets entirely, the main dietary sources of Vitamin D are mushrooms and fortified foods, such as plant-based kinds of milk.

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent and has little to do with diet as most Vitamin D (which is actually a hormone and not a vitamin) is made in our skin through a reaction with the sun. For those living more than 37 degrees latitude north or south of the equator, Vitamin D is only made via sun-exposed skin between late spring and early fall, not in the cooler months. Most people who don't make enough Vitamin D need supplementation since few people get enough from diet alone, regardless of the type of diet they eat. In addition to location, the following also increase the risk of vitamin D deficiency: obesity, cancer, darker skin pigmentation, pregnancy, institutionalization, and anyone with limited sun exposure. Dietary sources of vitamin D include fortified foods (dairy and plant-based kinds of milk), oily fish and seafood, egg yolks, mushrooms, animal fat, and liver. For those eating WFPB diets entirely, the main dietary sources of Vitamin D are mushrooms and fortified foods, such as plant-based kinds of milk.

Where do you get your Iron?

Iron deficiency is prevalent throughout the world and affects women and children much more commonly than men. The global prevalence of iron deficiency among women is 25 percent. The main causes of deficiency are low dietary intake, reduced absorption, and blood loss. In developed countries, blood loss is the predominant cause, whereas dietary intake plays a larger role in developing countries. Iron is perhaps one of the most interesting minerals in the diet as numerous factors affect our absorption and homeostasis.

Iron deficiency is prevalent throughout the world and affects women and children much more commonly than men. The global prevalence of iron deficiency among women is 25 percent. The main causes of deficiency are low dietary intake, reduced absorption, and blood loss. In developed countries, blood loss is the predominant cause, whereas dietary intake plays a larger role in developing countries. Iron is perhaps one of the most interesting minerals in the diet as numerous factors affect our absorption and homeostasis.

There are two types of dietary iron-heme and non-heme iron. Heme iron is present solely in animal foods as it comes fromhemoglobin and myoglobin. Non-heme iron is present in both plant and animal foods. Heme iron is more readily absorbed than non-heme iron, and this absorption is not subject to as many checks and balances as non-heme iron. Depending on iron balance, this can be a good or bad thing. Additionally, the literature has shown the association of heme iron intake with increased risk of coronary heart disease, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, and stomach cancer. Non-heme iron absorption depends on the current iron balance in the body and is affected by inhibitors (e.g., phytates, polyphenols, calcium, proteins) and enhancers (e.g., ascorbic acid, muscle tissue, non-digestible carbohydrates) of absorption.

Ascorbic acid (aka. Vitamin C) is the best enhancer of iron absorption for those eating plant-based diets. Deficiencies of riboflavin and Vitamin A, chronic inflammation, and obesity can also lead to iron deficiency through a variety of mechanisms. For those getting the majority of their iron intake from plant-based, non-heme sources, the following are some tips to help you consume and absorb more iron:

- Eat plant-based foods containing iron such as beans, tofu, dried fruits, greens, oatmeal, quinoa, amaranth, olives, mushrooms, unpeeled potatoes, nuts (cashews, pine nuts, macadamias) and seeds (pumpkin, sesame, hemp seed,flaxseed), dark chocolate, and fortified grain products like breads and cereals.

- Eat foods with ascorbic acid (aka. Vitamin C) with iron-containing foods to increase absorption. Vitamin C rich foods include citrus, pomegranate, tomatoes, cantaloupe, kiwi, broccoli, cauliflower, peppers, papaya, berries, lychee, pineapple, mango, green leafy veggies, and guava. Vitamin C degrades quickly with cooking and storage, so make sure to eat these foods fresh or shortly after cooking to get the most Vitamin C.

- Eat a variety of dark greens rather than relying on just one type. Don't rely solely on spinach for iron. While spinach contains many healthful nutrients, the oxalates in spinach interfere with absorption of iron. The techniques included in this section can help with iron absorption from spinach to some degree; however, it is better to opt for other dark, leafy greens if specifically looking for good sources of absorbable, non-heme iron. Cook in cast iron using acidic and/or ascorbic acid rich ingredients.

- Avoid coffee, tea, and wine with meals as polyphenols and tannins interfere with iron absorption.

- Avoid calcium supplements (or calcium-rich foods) one hour before and 2 hours after iron supplements or iron-rich foods to prevent the calcium and iron blocking the absorption of each other. For infants, beans and lentils are an ideal first food (beginning at age 6 months and beyond) because they are rich in iron.

Where do you get your Fiber, Folate, Potassium, Magnesium, and Vitamins A, C, and E?

OK, so maybe no one will ask you where you are getting these nutrients-but maybe they should. The SAD and other unhealthy diets that lead to overweight, obesity, and other chronic diseases are generally low in these nutrients and high in

saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, added sugars, and ultra-processed foods. Eating a balanced, predominantly WFPB diet means that you will not need to worry about getting enough of these nutrients often lacking in less healthy diets.

OK, so maybe no one will ask you where you are getting these nutrients-but maybe they should. The SAD and other unhealthy diets that lead to overweight, obesity, and other chronic diseases are generally low in these nutrients and high in

saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, added sugars, and ultra-processed foods. Eating a balanced, predominantly WFPB diet means that you will not need to worry about getting enough of these nutrients often lacking in less healthy diets.

Article Review

Advance to Unit 3

Complete your submission to advance to the next Unit.