UNIT 3 |

OBJECTIVES:

REFERENCES:

- Introduce the Diabetes diet blueprint to assist in the remission and reversal of diabetes type 2

- Discuss the most misunderstood macronutrient

- Identify other sources of sugar

- Describe the mechanism by which fiber is helping patients with diabetes in general

- Discuss the Glycemic index and Glycemic load

REFERENCES:

- Kick Diabetes Essentials, Brenda Davis, RD

- Nutrition Facts, Michael Greger, MD

- Nutrition Guide for Clinicians, Neal Barnard, MD

Diabetes Diet Blueprint

FOOD GROUPS |

OPTIMAL SERVINGS / DAY |

FOOD EXAMPLES AND SERVING SIZES |

CALCIUM RICH FOODS 5-8 SERVINGS PER DAY |

Nonstarchy Vegetables |

5 or more 7+ even better! |

Raw or cooked vegetables, ½ cup (125 ml); raw leafy vegetables, 1 cup (250 ml); vegetable juice, ½ cup (125 ml) |

Bok choy, broccoli, collard greens, kale, napa cabbage, indigenous leafy greens, okra, 1 cup (250 ml) cooked, or 2 cups (500 ml) raw |

Fruits |

3 or more |

Whole Fruit, medium-sized, fruit, raw or cooked, ½ cup (125 ml); dried fruit, ¼ cup (60 ml) |

Oranges, 2: dried figs, ½ cup (125 ml) |

Legumes |

3 or more |

Cooked beans, peas, or lentils, bean pasta, or tofu or tempeh, ½ cup (125 ml); raw peas or sprouted lentils, mung beans, or peas, 1 cup (250 ml); vegetarian meat substitute, 1 oz (30 g); fortified soy milk, 1 cup (250 ml) |

Black or white beans, 1 cup (250 ml); calcium-set tofu, ½ cup (125 ml); fortified soy milk or soy yogurt, ½ cup (125 ml) |

Whole grains and Starchy vegetables |

2 or more |

Cooked whole grains or starchy vegetables, ½ cup (125 ml); 1 oz (30 g) very dense whole-grain bread |

- |

Nuts and Seeds |

2 - 3 |

2 Tbsp (30 ml) nuts or seeds; 1 Tbsp (15 ml) nut or seed butter |

Almonds or chia or sesame seeds, ¼ cup (60 ml); almond butter or tahini, 2 Tbsp (30 ml) |

Herbs and Spices |

3 or more |

¼ - ½ tsp (1-2 ml) ground spice; 1 tsp (5 ml) dried herbs; 1 Tbsp (15ml) fresh herbs |

- |

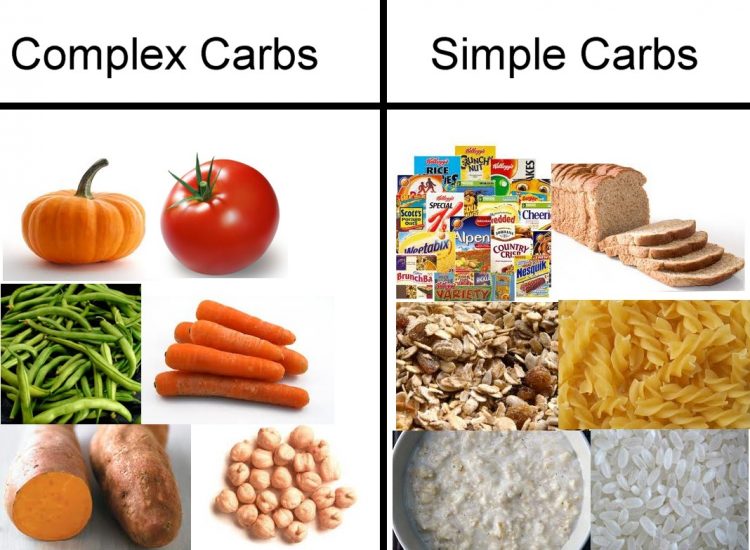

The Carbs

Carbohydrate-rich foods are the most important sources of food energy in the world. Across the globe, intakes range from 40-80 percent of calories, with people in developing countries tending toward the higher end and those in Western nations falling near the lower end of the range. So why are carbohydrates commonly viewed as villains by popular nutrition authorities and consumers? The answer lies in the quality of the carbohydrates. Because the vast majority of carbohydrates consumed by populations in which obesity and diabetes are prevalent have been refined, all high-carbohydrate foods are considered suspect. This is a mistake. By minimizing carbohydrates, you reduce the intake of beneficial components associated with whole plant foods: fiber, phytochemicals, antioxidants, plant sterols, pre- and probiotics, vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids. People who rely on whole plant foods for most of their carbohydrates are consistently protected against obesity and diabetes.

Carbohydrates are most the Misunderstood Macronutrient

Refined carbohydrates are extracted from plant foods and have been stripped of most of their beneficial components by food-processing techniques. There are two main categories of refined carbohydrates:

Refined carbohydrates are extracted from plant foods and have been stripped of most of their beneficial components by food-processing techniques. There are two main categories of refined carbohydrates:

- Starches

- Sugars

|

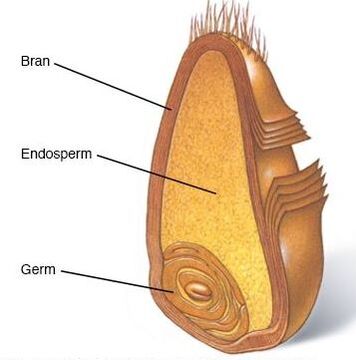

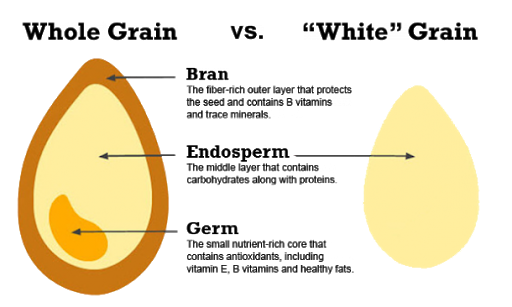

The bran is the outer husk, which protects the contents of the grain. Although the bran provides nutrients and phytochemicals, its main claim to fame is fiber. What is left after the germ and bran are removed is called the endosperm, which is mainly starch, some protein, and a miniscule amount of vitamins and minerals. In the process of turning wheat kernels into white flour, 70-90 percent of the vitamins, minerals, and fiber are lost. To add insult to injury, a two-hundredfold to three-hundredfold loss in phytochemicals occurs.

|

Granted, some nutrients may be added back. For example, when wheat or rice is refined into flour, it is often enriched with four B vitamins (thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and folic acid) and the mineral iron. However other vitamins and minerals (such as vitamin B6 pantothenic acid, vitamin E, selenium, magnesium, zinc, potassium, manganese, and boron) are not added back, nor are the phytochemicals or fiber. And, of course, no one eats a bowl of plain white flour. Varying amounts of sugar, salt, fat, colors, flavors, and preservatives are added to enhance the palatability and appearance of the final product, which is then consumed as bread, cake, cereal, cookies, crackers, pasta, pastries, pretzels, pancakes, or other flour products. So not only are the most protective parts of the plant removed, but also a number of potentially harmful ingredients are added. This is a risky trade-off for human health.

To prevent or reverse diabetes, rely on high-quality carbohydrates, such as unrefined whole plant foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds).

To prevent or reverse diabetes, rely on high-quality carbohydrates, such as unrefined whole plant foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds).

|

Minimize or avoid low-quality carbohydrates, such as refined starches (white flour products and concentrated starches, such as cornstarch) and refined sugars and syrups. When carbohydrate-rich foods are refined, the fiber that slows the absorption of carbohydrates into the bloodstream is removed and their glycemic index rises. In addition, the nutrients needed to metabolize those carbohydrates are shaved away, so the body is less able to deal with the fast influx of these energy-giving nutrients.

|

Eliminate processed foods with added refined flours and sugars, shift away from packaged foods, and leave the skin on the starchy vegetables you eat. Choose black, red or brown rice instead of white rice and intact whole grains instead of flour products. To time-tune diet even further, select lower GI (Glycemic Index) foods within each food category. In addition to the quality of the carbohydrates you eat, there's also the issue of quantity: Important considerations include the percentage of total calories as carbohydrate, the amount or grams of carbohydrates consumed each day, and the spacing or regularity of carbohydrate intake. If most of your food provides high-quality, unrefined carbohydrates, the range of intake that will support and promote health is quite wide. Established diabetes guidelines recommend 45-60 percent of calories from carbohydrates. The upper limit can be successfully extended to 70 percent (or slightly higher) with very high-fiber diets.

|

On the other hand, if you eat mostly poor-quality, refined carbohydrates, you may see health benefits from cutting carbs, especially if fat and protein sources are carefully selected. However, a healthier approach would be to swap the low-quality refined carbohydrates for high-quality unrefined carbohydrates. Dipping below the 45 percent mark is not recommended, as low carbohydrate intakes are associated with escalating intakes of saturated fat and animal protein.

|

Your total carbohydrate intake and the spacing and regularity of intake can impact body weight and blood glucose control. If your goal is weight loss, portion sizes of carbohydrate-rich foods will need to be controlled. If you're consuming a whole-foods, plant-based, weight-loss diet of 1,400-1,800 calories, your upper limit for carbohydrate would be 245-315g (based on 70 percent of calories from carbohydrates). This amounts to 80-100 grams of carbohydrate per meal. To put this into perspective, l cup (250 ml) of beans or whole grains has about 40 grams; one large apple, about 30 grams; l cup (250 ml) of blueberries, about 20 grams; and I cup (250 ml) of broccoli, about 10 grams. Although carbohydrate counting is not necessary, keeping track of your intake for a week or two can help you become more familiar with the carbohydrate content of specific foods.

The quantity of carbohydrates you consume will affect your blood glucose levels, even when those carbohydrates come from whole plant foods. You'll want to space your intake throughout the day to help keep blood glucose levels relatively stable and avoid extreme highs and lows. To accomplish this, eat regular, balanced meals. Although distributing carbohydrate intake throughout the day is most important for individuals who take insulin, it can also be helpful for anyone who is trying to improve blood glucose control. One simple way of doing this is to include one or two servings of carbohydrate-rich foods per meal, depending on your caloric needs. Most meals will include a whole grain or starchy vegetable. For more aggressive weight-loss regimens, sufficient carbohydrates can be obtained from legumes and non starchy vegetables or fruits.

The quantity of carbohydrates you consume will affect your blood glucose levels, even when those carbohydrates come from whole plant foods. You'll want to space your intake throughout the day to help keep blood glucose levels relatively stable and avoid extreme highs and lows. To accomplish this, eat regular, balanced meals. Although distributing carbohydrate intake throughout the day is most important for individuals who take insulin, it can also be helpful for anyone who is trying to improve blood glucose control. One simple way of doing this is to include one or two servings of carbohydrate-rich foods per meal, depending on your caloric needs. Most meals will include a whole grain or starchy vegetable. For more aggressive weight-loss regimens, sufficient carbohydrates can be obtained from legumes and non starchy vegetables or fruits.

WHAT ARE REFINED CARBOHYDRATES?

Refined carbohydrates are made from processed grains (such as white flour), other processed starchy foods (such as peeled potatoes), or processed sweeteners (such as white or brown sugar). In other words, these are low-quality carbohydrate sources. Examples of foods rich in refined starches are breads or pastas made with white flour. Examples of foods rich in refined sugars are sodas, candies, and sugar-sweetened jams or jellies.

Refined carbohydrates are made from processed grains (such as white flour), other processed starchy foods (such as peeled potatoes), or processed sweeteners (such as white or brown sugar). In other words, these are low-quality carbohydrate sources. Examples of foods rich in refined starches are breads or pastas made with white flour. Examples of foods rich in refined sugars are sodas, candies, and sugar-sweetened jams or jellies.

WHAT ARE UNREFINED CARBOHYDRATES?

Unrefined carbohydrates are naturally present in whole plant foods, such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. In other words, these are high-quality carbohydrate sources. Examples of foods rich in unrefined starches are barley, quinoa, sweet potatoes, and beans. Examples of unrefined foods with natural sugars are fruits, dried fruits, and nonstarchy vegetables, such as broccoli, cucumbers, leafy greens, peppers, and tomatoes.

Unrefined carbohydrates are naturally present in whole plant foods, such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. In other words, these are high-quality carbohydrate sources. Examples of foods rich in unrefined starches are barley, quinoa, sweet potatoes, and beans. Examples of unrefined foods with natural sugars are fruits, dried fruits, and nonstarchy vegetables, such as broccoli, cucumbers, leafy greens, peppers, and tomatoes.

All about Sugar

|

Humans have a soft spot for sweets. We were born that way, and for good reason. In nature, sweetness generally signals safety, while bitterness serves as a warning flag. It would be difficult to consume excessive sugar when eating foods in the form in which they are grown. Yet when sugars are extracted and concentrated, then added to ultra processed foods, our hardwiring for sweets works against us. Our appetite control center becomes unhinged, and satiety signals fail to protect us from overconsumption.

|

In 1700, annual per capita sugar consumption averaged 4 pounds (1.8 kg) per person per year in the UK. It was not until the mid 1800s that sugar became a common part of everyday diets. Since 2015, total added sugar intakes have hovered around 15 percent of calories in the Us, down from 18 percent in 1999 The average American adult now consumes about 19 teaspoons (80 g) per day. The US Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee recommends limiting added sugars to not more than 10 percent of total calories (12 teaspoons/50 g in a 2,000-calorie diet). The World Health Organization concurs but adds that greater health benefits would be achieved by lowering intake to not more than 5 percent of calories (6 teaspoons/25 g in a 2,000-calorie diet). Actual intakes exceed all of these recommendations.

How damaging is sugar to health? Sugar itself is not inherently harmful. In fact, when it is naturally present in the matrix of a whole food, its the preferred fuel for the human body, and we are well equipped to handle it. It's excess sugar that's the issue, particularly when it comes from concentrated sweeteners. While its the dose that makes the poison, whenever concentrated sugars are involved, It is best to minimize their intake or avoid them completely.

The adverse effects of sugar are most pronounced when there is a surplus of calories. It is particularly problematic when consumed in the absence of fiber, as is the case with beverages and many ultra processed foods. Diets containing a high proportion of calories as concentrated sugars (and, in most instances, other relined carbohydrates) are associated with a laundry list of adverse health consequences:

Poor nutrition. Sugar, which provides significant calories but insignificant nutrients, can crowd out more nutrient-dense foods. This may result in an overall reduction in micronutrient intakes and potentially shortfalls.

Hypertension. There is growing evidence that excessive sugar intake may raise blood pressure. A meta-analysis reported an 8 percent increase in risk for every serving of sugar-sweetened beverage consumed.

High triglycerides. High-sugar diets increase triglycerides, especially when simple sugars exceed 20 percent of energy. Fructose has the most profound impact of all sugars. The effect appears to be even greater in men, in sedentary and overweight individuals, and in people with metabolic syndrome or diabetes. High triglycerides can increase the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Decreased HDL cholesterol. Most but not all studies show reductions in beneficial HDL cholesterol with increasing sugar intake. Fructose appears more potent than sucrose in reducing HDL cholesterol levels.

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Chronic, excessive sugar intake can result in sustained, elevated blood glucose levels, increased insulin output, and insulin resistance.

How damaging is sugar to health? Sugar itself is not inherently harmful. In fact, when it is naturally present in the matrix of a whole food, its the preferred fuel for the human body, and we are well equipped to handle it. It's excess sugar that's the issue, particularly when it comes from concentrated sweeteners. While its the dose that makes the poison, whenever concentrated sugars are involved, It is best to minimize their intake or avoid them completely.

The adverse effects of sugar are most pronounced when there is a surplus of calories. It is particularly problematic when consumed in the absence of fiber, as is the case with beverages and many ultra processed foods. Diets containing a high proportion of calories as concentrated sugars (and, in most instances, other relined carbohydrates) are associated with a laundry list of adverse health consequences:

Poor nutrition. Sugar, which provides significant calories but insignificant nutrients, can crowd out more nutrient-dense foods. This may result in an overall reduction in micronutrient intakes and potentially shortfalls.

Hypertension. There is growing evidence that excessive sugar intake may raise blood pressure. A meta-analysis reported an 8 percent increase in risk for every serving of sugar-sweetened beverage consumed.

High triglycerides. High-sugar diets increase triglycerides, especially when simple sugars exceed 20 percent of energy. Fructose has the most profound impact of all sugars. The effect appears to be even greater in men, in sedentary and overweight individuals, and in people with metabolic syndrome or diabetes. High triglycerides can increase the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Decreased HDL cholesterol. Most but not all studies show reductions in beneficial HDL cholesterol with increasing sugar intake. Fructose appears more potent than sucrose in reducing HDL cholesterol levels.

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Chronic, excessive sugar intake can result in sustained, elevated blood glucose levels, increased insulin output, and insulin resistance.

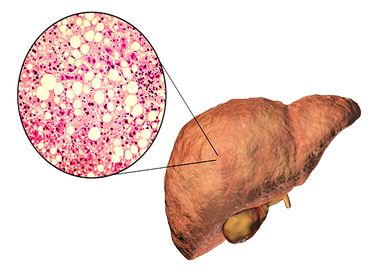

This means that the body fails to respond properly to insulin, and blood glucose is not efficiently cleared. There is increased risk for metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes. Fructose is associated with increase levels of visceral fat around vital organs, further increasing insulin resistance and blood glucose, metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, and levels of visceral fat (fat in and around vital organs), further increasing insulin resistance.

Increased cancer risk. There is limited evidence that high intakes of sucrose increase in the risk of colorectal cancer. One study reported a greater than two-fold increase in the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women who were regular consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages compared to women who seldom or never consume them.

Overconsumption, overweight, and obesity. Increasing added sugars, especially from beverages, can result in an increase in total energy consumption, leading to overweight, obesity, and a higher risk of chronic disease. Poor dental health. High sugar intakes are strongly associated with dental caries and reduced dental health.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is a key driver of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The prevalence is approximately 43 percent in people with impaired glucose tolerance and 62 percent in those with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Excessive sugar intake has seen associated with NAFLD, with excessive fructose intake being especially problematic.

Gout. Excess sugar intake, particularly from sugar-sweetened beverages, is positively associated with increased uric acid levels and gout. Fructose appears to be especially effective at driving up uric acid levels.

Inflammation. Sugar excesses have been shown to increase inflammation, especially in insulin-sensitive tissues. Proinflammatory molecules may rise with elevated blood Glucose levels.

Increased formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Limited research suggests that fructose is linked to AGE formation within body cells and is approximately eight times more likely to form these compounds than glucose. AGEs contribute to numerous disease processes and accelerate aging.

Increased cancer risk. There is limited evidence that high intakes of sucrose increase in the risk of colorectal cancer. One study reported a greater than two-fold increase in the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women who were regular consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages compared to women who seldom or never consume them.

Overconsumption, overweight, and obesity. Increasing added sugars, especially from beverages, can result in an increase in total energy consumption, leading to overweight, obesity, and a higher risk of chronic disease. Poor dental health. High sugar intakes are strongly associated with dental caries and reduced dental health.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is a key driver of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The prevalence is approximately 43 percent in people with impaired glucose tolerance and 62 percent in those with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Excessive sugar intake has seen associated with NAFLD, with excessive fructose intake being especially problematic.

Gout. Excess sugar intake, particularly from sugar-sweetened beverages, is positively associated with increased uric acid levels and gout. Fructose appears to be especially effective at driving up uric acid levels.

Inflammation. Sugar excesses have been shown to increase inflammation, especially in insulin-sensitive tissues. Proinflammatory molecules may rise with elevated blood Glucose levels.

Increased formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Limited research suggests that fructose is linked to AGE formation within body cells and is approximately eight times more likely to form these compounds than glucose. AGEs contribute to numerous disease processes and accelerate aging.

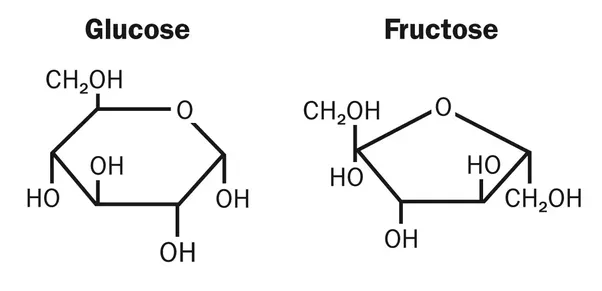

What is Fructose?

|

Excess fructose appears to be even more damaging than excess glucose. When it is consumed in excess, it promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, elevated triglycerides, increased LDL cholesterol, insulin resistance, elevated blood pressure, visceral fat accumulation, and the formation of advanced glycation end products more sharply than glucose.

|

Understanding the metabolic fate of fructose helps to explain this phenomenon. For many years scientists believed that fructose was metabolized exclusively by the liver. More recent evidence suggests that much of the fructose we consume is converted into glucose and other metabolites in the intestines. However, if fructose intake is very high, the intestines can't keep up and the excess is either shuttled to the liver for processing or it passes into the colon where it feeds harmful bacteria. Every cell in the human body can use glucose for energy while fructose, once in the bloodstream, is metabolized almost exclusively by liver cells. In the liver, the preferred fate of fructose is to replenish glycogen stores. In fact, fructose is a better substrate for making glycogen than glucose. Once liver glycogen is replenished, any additional fructose is converted into triglycerides or fatty acids and stored in fat cells , muscles, or vital organs. As you may recall, when excess fat is stored in the muscles or vital organs, lipotoxicity, a major driver of insulin resistance, can result.

On a positive note, there is a rapid response to fructose restriction. In a study of children with features of metabolic syndrome, just nine days of fructose restriction (with an equal calorie substitution for complex carbohydrates) resulted in reductions in fasting glucose and insulin levels, improved glucose tolerance, and better lipid profiles. Liver fat concentrations decreased by 22 percent on average. The conversion of carbohydrates to fatty acids, a process known as de novo lipogenesis, was reduced by 56 percent.

|

Similarly in a metabolic study of adult men, de novo lipogenesis was almost 19 percent when the men were fed a high-fructose diet (25 percent of calories from fructose) compared to 11 percent when they were eating a low-fructose diet (less than 4 percent of calories from fructose). Liver fat concentration also significantly increased when fructose intake was high.

|

The problem is not fructose from fruits and vegetables. The human body is well equipped to handle the relatively small amounts of fructose naturally present in whole plant foods. However, when the diet is loaded with concentrated fructose, the body's capacity to handle it quickly becomes overwhelmed.

Its interesting to note that between 1970 and 1995, sugar intake increased by 19 percent, but the most notable change was not in the amount of sugar consumed but rather in the type of sugar consumed. While intake of sucrose (in the form of table sugar from sugarcane and beets) declined by 38 percent, the intake of high-fructose corn sweeteners increased by 387 percent. By 2007, 45 percent of total added sugars came iron table sugar (sucrose), 41 percent came from high-fructose corn syrup, and 14 percent came from glucose syrup, pure glucose, and honey.

The fructose content of a serving of fruit is 2-12 grams, averaging about 6 grams. Fruit juices can contain higher amounts. The fructose content of a 12-ounce (375-ml) soda, regardless of whether it is sweetened by high-fructose corn syrup or sucrose, is about 20 grams or slightly more. Note that sucrose is halt glucose, halt fructose. Essentially, our two most common sweeteners (sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup) provide roughly equal amounts of glucose and fructose.

The main difference between high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose is that in sucrose the glucose and fructose are bound together and must be cleaved apart by an enzyme or acid before being absorbed. In high-fructose corn syrup, the fructose is not bound to glucose; instead, both the fructose and glucose are present as single sugars (known as free monosaccharides). Preliminary evidence suggests that blood levels of fructose are higher with the consumption of high-fructose corn syrup compared with equal amounts of sucrose from beverages.

Work on Sugar Habits

Sugar is everywhere, and most people were introduced to it early in life, so it's normal to expect sweet flavors in your foods. The good news is that you can overcome the hold that sugar has on you.

REWIRE YOUR TASTE BUDS

Sugar is addictive. It increases a brain chemical called dopamine, which is associated with the brain's reward system. This is the same system that is triggered by drugs, alcohol and nicotine. While sugar provokes a less dramatic surge in dopamine than drugs, its effect is still quite profound, especially with large intakes. Excess sugar causes a spike in dopamine that makes you feel good, but when dopamine falls, you crave more sugar. The cycle leads to tolerance, so you need more sugar to get the same reward.

The good news is, by decreasing your sugar intake, your taste buds can readjust and your brain can be rewired to crave sugar less. if you are sugarholic, you may need to reduce intake gradually. Cut intake in half for a week, then in half again, until you are using little or none. If need be, some of the sugar can be replaced with a natural noncaloric sweetener while your taste buds are adjusting. However, this too should be limited over time because your taste buds required a reduction of all things sweet in order to appreciate the natural flavors in foods. The advantage of the natural noncaloric sweetener over sugar is that it won't cause a spike in blood glucose.

Sugar is addictive. It increases a brain chemical called dopamine, which is associated with the brain's reward system. This is the same system that is triggered by drugs, alcohol and nicotine. While sugar provokes a less dramatic surge in dopamine than drugs, its effect is still quite profound, especially with large intakes. Excess sugar causes a spike in dopamine that makes you feel good, but when dopamine falls, you crave more sugar. The cycle leads to tolerance, so you need more sugar to get the same reward.

The good news is, by decreasing your sugar intake, your taste buds can readjust and your brain can be rewired to crave sugar less. if you are sugarholic, you may need to reduce intake gradually. Cut intake in half for a week, then in half again, until you are using little or none. If need be, some of the sugar can be replaced with a natural noncaloric sweetener while your taste buds are adjusting. However, this too should be limited over time because your taste buds required a reduction of all things sweet in order to appreciate the natural flavors in foods. The advantage of the natural noncaloric sweetener over sugar is that it won't cause a spike in blood glucose.

STEER CLEAR OF BEVERAGES WITH ADDED SUGARS

The average 12-ounce (375-ml) serving of soda or fruit drink packs about 150 calories from sugar. That is close to 10 teaspoons (40 grams) of sugar per serving - and some drinks have even more. Consuming sugar-sweetened beverages is strongly linked to weight gain and diabetes risk. If you add just one 12-ounce (375-ml) can of regular soft drink to your daily diet, you can expect to add about 15 pounds (6.9 kg) per year. While you might imagine that you would eliminate calories elsewhere, this is not always the case. When you drink your calories, your body fails to register those calories with the appetite control center the way it does when you eat solid food.

The average 12-ounce (375-ml) serving of soda or fruit drink packs about 150 calories from sugar. That is close to 10 teaspoons (40 grams) of sugar per serving - and some drinks have even more. Consuming sugar-sweetened beverages is strongly linked to weight gain and diabetes risk. If you add just one 12-ounce (375-ml) can of regular soft drink to your daily diet, you can expect to add about 15 pounds (6.9 kg) per year. While you might imagine that you would eliminate calories elsewhere, this is not always the case. When you drink your calories, your body fails to register those calories with the appetite control center the way it does when you eat solid food.

The bottom line is simple: avoid all sugar-sweetened beverages, including soda, energy drinks. sports beverages, sweetened coffee or tea beverages, fruit drinks, and sweet alcoholic beverages. Sugar-sweetened beverages contribute to the development of insulin resistance, prediabetes, and diabetes because these are conditions of abnormal glucose metabolism and high blood sugar. The last thing you want to do when you have these conditions is to consume highly absorbable liquid sugar.

EAT WHOLE FOODS INSTEAD OF PACKAGED FOOD

About 90 percent of added sugars consumed in Westernized countries come from packaged foods. Cutting out down on these foods will dramatically reduce sugar intake. When sugar is within the matrix of a whole food that is rich in fiber, it is safe to consume.

You cant' always trust your instincts when selecting packaged foods. Often products that you might assume are low in sugar are not. For example, barbeque sauce, ketchup, and many other ready-made sauces get most of their calories from sugar, as do many low-fat salad dressings. Instant oatmeal, breakfast bars, granola bars, protein bars, bottled smoothies, canned baked beans, canned fruits, and ready-to-eat breakfast cereals (even healthy-sounding ones) are often high in sugar.

About 90 percent of added sugars consumed in Westernized countries come from packaged foods. Cutting out down on these foods will dramatically reduce sugar intake. When sugar is within the matrix of a whole food that is rich in fiber, it is safe to consume.

You cant' always trust your instincts when selecting packaged foods. Often products that you might assume are low in sugar are not. For example, barbeque sauce, ketchup, and many other ready-made sauces get most of their calories from sugar, as do many low-fat salad dressings. Instant oatmeal, breakfast bars, granola bars, protein bars, bottled smoothies, canned baked beans, canned fruits, and ready-to-eat breakfast cereals (even healthy-sounding ones) are often high in sugar.

IF YOU EAT PACKAGED FOODS, READ THE LABEL AND SELECT PRODUCTS WITH LESS ADDED SUGAR

Go to the nutrition Facts panel and check the serving size - servings are often smaller that you might imagine. To determine the number of teaspoons of sugar per serving of food, find the total grams of sugar and divide this number by four. The precise conversion of 4.2 grams per teaspoon; rounding down to four makes for easier calculation. So, 16 grams of sugar in a serving of food would equal about 4 teaspoons (20 ml). Remember that 1 gram of sugar has 4 calories. So, if a serving of a food has 100 calories and 10 grams of sugar, that means the food derives 40 percent of its calories from sugar (10 x 4 / 100).

The total sugar listing in the Nutrition Facts panel does not distinguish between the sugars naturally present in food and added sugars. On a label that does not list added sugars, it can be difficult to know how much of the total sugar comes from natural sources (such as fruit) and how much of the total sugar. if there are no natural sugars (from fruits, vegetables, or dairy products), then the sugar listed is all added sugar. The exception to this rule is fruit juice concentrate, which is included as an added sugar.

If there are natural sugars from fruits, dried fruits, or even vegetables (such as tomatoes), then some further detective work is called for in order to figure out how much added sugar might be present. you will need to scrutinize the ingredients list, and although this will not tell you the precise division of natural and added sugars, it will provide some helpful information. Ingredients are listed in descending order according to their weight. If sugar is near the top of the list, this is a clue that added sugars are high. Some manufacturers try to push sugars lower down on the ingredients list by using smaller amounts of several different sweeteners, some of which consumers might not even recognize as sugar. Of course, you will see the usual suspects, such as beet sugar, brown sugar, cane sugar, coconut sugar, confectioner's sugar, corn sugar, date sugar, invert sugar, turbinado sugar, and other sugars. You may find a variety of syrups, such as agave syrup, brown rice syrup, corn syrup, corn syrup solids, high-fructose corn syrup, malt syrup, and maple syrup, along with other easily recognizable sugars, such as honey and molasses. However, you may also notice ingredients such as dextrin and maltodextrin or ones that end in "ose," such as dextrose, fructose, glucose, lactose, and maltose. All of these are sugars. The following tips will help you keep added sugars to a bare minimum:

Go to the nutrition Facts panel and check the serving size - servings are often smaller that you might imagine. To determine the number of teaspoons of sugar per serving of food, find the total grams of sugar and divide this number by four. The precise conversion of 4.2 grams per teaspoon; rounding down to four makes for easier calculation. So, 16 grams of sugar in a serving of food would equal about 4 teaspoons (20 ml). Remember that 1 gram of sugar has 4 calories. So, if a serving of a food has 100 calories and 10 grams of sugar, that means the food derives 40 percent of its calories from sugar (10 x 4 / 100).

The total sugar listing in the Nutrition Facts panel does not distinguish between the sugars naturally present in food and added sugars. On a label that does not list added sugars, it can be difficult to know how much of the total sugar comes from natural sources (such as fruit) and how much of the total sugar. if there are no natural sugars (from fruits, vegetables, or dairy products), then the sugar listed is all added sugar. The exception to this rule is fruit juice concentrate, which is included as an added sugar.

If there are natural sugars from fruits, dried fruits, or even vegetables (such as tomatoes), then some further detective work is called for in order to figure out how much added sugar might be present. you will need to scrutinize the ingredients list, and although this will not tell you the precise division of natural and added sugars, it will provide some helpful information. Ingredients are listed in descending order according to their weight. If sugar is near the top of the list, this is a clue that added sugars are high. Some manufacturers try to push sugars lower down on the ingredients list by using smaller amounts of several different sweeteners, some of which consumers might not even recognize as sugar. Of course, you will see the usual suspects, such as beet sugar, brown sugar, cane sugar, coconut sugar, confectioner's sugar, corn sugar, date sugar, invert sugar, turbinado sugar, and other sugars. You may find a variety of syrups, such as agave syrup, brown rice syrup, corn syrup, corn syrup solids, high-fructose corn syrup, malt syrup, and maple syrup, along with other easily recognizable sugars, such as honey and molasses. However, you may also notice ingredients such as dextrin and maltodextrin or ones that end in "ose," such as dextrose, fructose, glucose, lactose, and maltose. All of these are sugars. The following tips will help you keep added sugars to a bare minimum:

- Purchase products labeled "unsweetened" or "no added sugar," such as nondairy milks, applesauce, nut butters, oatmeal, and canned fruits.

- Compare products such as tomato sauce, salad dressings, and condiments, and select a product with no added sugar or with the least added sugar.

- Don't let words such as "natural" or "organic" fool you. These words are no guarantee of low sugars.

- If you're buying a sweetened product, such as a bar or cereal, select one that uses fresh or dried fruit as the primary sweetener instead of sugars or syrups.

IS THERE SUCH THING AS HEALTHY SUGAR

The simple truth is that the differences between various concentrated sugars are of relatively minor consequence to health. Most sugars are essentially glucose, fructose, or some combination of the two. Although a few sweeteners contain tiny amounts of nutrients, you would have to eat far more than you should to make a significant contribution to your nutritional needs.

The simple truth is that the differences between various concentrated sugars are of relatively minor consequence to health. Most sugars are essentially glucose, fructose, or some combination of the two. Although a few sweeteners contain tiny amounts of nutrients, you would have to eat far more than you should to make a significant contribution to your nutritional needs.

|

One notable exception is blackstrap molasses, which is an impressive mineral source. For example, 2 tablespoons (30 ml) of blackstrap molasses provides 353 milligrams of calcium, 7.2 milligrams of iron, and 1,023 milligrams of potassium-more calcium than 1 cup of milk, more iron than an 8-ounce steak, and more potassium than two large bananas.

|

|

Date sugar is made from dried and ground dates, so its a whole-food sugar, which is preferable to refined sugars. Coconut sugar is dried coconut nectar, and it is more nutrient dense than typical refined sugars. Regardless, the bottom line is that sugar is sugar. Even the sugars derived from whole-food sources, such as date or coconut sugar, will have a significant impact on blood glucose and should be minimized. The best advice is to kick the sugar habit and get used to foods with less sweetness.

|

It is convenient and relatively economical. Eat fruit whole, chop it into a fruit salad, slice it and serve with a little nut butter, freeze it and blend it to the texture of ice cream or sorbet, or bake it. Step outside of your comfort zone and try fruits that are new to you. Dried fruits can be used in place of sugar in homemade cereals, baked goods, desserts, and treats. Although they are naturally high in sugar, dried fruits when used judiciously, are healthful, high-fiber, nutrient-dense alternatives to sugar.

TAKE ADVANTAGE OF HERBS AND SPICES TO FLAVOR FOODS INSTEAD OF SUGAR

Sugar Use vanilla beans or vanilla extract, citrus zest, or spices, such as allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, and star anise to bring out the natural sweetness in foods. Not only are these seasonings sugar-free, but they also are great sources of antioxidants and phytochemicals.

Sugar Use vanilla beans or vanilla extract, citrus zest, or spices, such as allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, and star anise to bring out the natural sweetness in foods. Not only are these seasonings sugar-free, but they also are great sources of antioxidants and phytochemicals.

|

Add them to cereals, puddings, baked goods, and beverages.

Some of them also work well in savory dishes. You can enhance the flavor of commonly sweetened savory foods, such as pasta sauce, with herbs and caramelized onion. Root vegetables, such as carrots and beets, also add sweetness to main and side dishes. |

HOW ABOUT ALTERNATIVE SWEETENERS?

Alternative sweeteners are divided into two categories: sugar alcohols and high intensity Sweeteners. Sugar alcohols are nutritive or caloric sweeteners (that is, they contain calories). High-intensity sweeteners are mostly non-nutritive or calorie. Sugar alcohols (also known as polyols) are a distinct category of sweet carbohydrates. Part of their chemical structure resembles a carbohydrate, while another part resembles alcohol. They are resistant to digestion, so they behave a lot like fiber. The effects are similar to those of oligosaccharides; they go undigested into the large intestine and are fermented by the bacteria that reside there. When consumed in large amounts, sugar alcohols can cause gastrointestinal distress, such as abdominal pain.

Alternative sweeteners are divided into two categories: sugar alcohols and high intensity Sweeteners. Sugar alcohols are nutritive or caloric sweeteners (that is, they contain calories). High-intensity sweeteners are mostly non-nutritive or calorie. Sugar alcohols (also known as polyols) are a distinct category of sweet carbohydrates. Part of their chemical structure resembles a carbohydrate, while another part resembles alcohol. They are resistant to digestion, so they behave a lot like fiber. The effects are similar to those of oligosaccharides; they go undigested into the large intestine and are fermented by the bacteria that reside there. When consumed in large amounts, sugar alcohols can cause gastrointestinal distress, such as abdominal pain.

|

Even though sugar alcohols exist naturally in foods such as fruits and vegetables, most are manufactured from starches and sugars and are used in processed foods. Because they provide on average about half the calories of other carbohydrates and are thought to be relatively safe, sugar alcohols are often considered excellent sugar substitutes for people with diabetes. However, in order to train your palate to prefer less sweet tastes, it is still best to minimize their use.

|

The most common sugar alcohols are erythritol, maltitol, sorbitol, and xylitol. Erythritol has the fewest calories at 0.2 calories per gram, while the other sugar alcohols range from 1.6-3 calories per gram (compared to 4 calories per gram for carbohydrates). Erythritol is the one sugar alcohol that tends to not have adverse digestive effects because it is mostly absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted in the urine rather than passing through into the large intestine. Although sugar alcohols do affect blood glucose, their impact is significantly less than that of other carbohydrates.

They are very shelf stable because they are not as likely as sugar to attract bacteria or mold. These attributes make sugar alcohols very attractive to food manufacturers. On food labels, sugar alcohol content is listed separately from other carbohydrates. If you're counting carbohydrates, you can omit sugar alcohols if the total content is 5 grams or less or if the sugar alcohol is erythritol. However, if the total is more than 5 grams, simply divide the total by two and add it to your carbohydrate count. For example, if you eat 10 grams of sugar alcohols, you would count only 5 grams. Sugar alcohols do not promote tooth decay, so they are the sweetener of choice in many dental hygiene products, such as toothpastes and mouth rinses. They also are used in breath mints and gums and in a variety of processed foods, such as ice cream, candy and fruit spreads. Products containing sugar alcohols are often labeled sugar-free. The second category of alternative sweeteners is high-intensity sweeteners. Some of these are artificial or synthetically produced while others are natural. Most are non-nutritive or essentially calorie-free. High-intensity sweeteners are regulated by national governments, and not all are permitted for use in all countries.

They are very shelf stable because they are not as likely as sugar to attract bacteria or mold. These attributes make sugar alcohols very attractive to food manufacturers. On food labels, sugar alcohol content is listed separately from other carbohydrates. If you're counting carbohydrates, you can omit sugar alcohols if the total content is 5 grams or less or if the sugar alcohol is erythritol. However, if the total is more than 5 grams, simply divide the total by two and add it to your carbohydrate count. For example, if you eat 10 grams of sugar alcohols, you would count only 5 grams. Sugar alcohols do not promote tooth decay, so they are the sweetener of choice in many dental hygiene products, such as toothpastes and mouth rinses. They also are used in breath mints and gums and in a variety of processed foods, such as ice cream, candy and fruit spreads. Products containing sugar alcohols are often labeled sugar-free. The second category of alternative sweeteners is high-intensity sweeteners. Some of these are artificial or synthetically produced while others are natural. Most are non-nutritive or essentially calorie-free. High-intensity sweeteners are regulated by national governments, and not all are permitted for use in all countries.

In the United States the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of six high-intensity artificial sweeteners: acesulfame-K, advantame, aspartame, neolame, saccharin, and sucralose. Of these six, aspartame is the only one that is considered nutritive because it contains calories. However, it is about two hundred times sweeter than sugar, so used in such small amounts that its considered calorie-free.

There are two approved high-intensity natural sweeteners. steviol glycosides and luo han guo (monk fruit) extracts. Both are non-nutritive or essentially calorie-free. Steviol glycosides, such as rebaudioside A (also called rebA), stevioside, rebaudioside D, or various mixtures of these compounds, are extracted from the stevia plant. These components are two hundred to four hundred times sweeter than sugar. While these constituents of stevia have been approved for use as sweeteners in the United States, the stevia leaf and crude stevia extracts have only been approved tor use as nutritional supplements and not as sweeteners. Although there is controversy about the safety and side effects of stevia, recent scientific studies have been largely favorable.

Stevia is approved for use in several countries and has been the principal non-nutritive sweetener used in Japan for several decades. Luo han guo, or monk fruit, is a fruit from southern China that has been used in Chinese medicine to treat coughs and sore throats and as a longevity aid. Monk fruit extracts contain a compound called mogrosides, which are 100-250 times sweeter than sugar.

The safety of high-intensity sweeteners is very controversial, although most health organizations, including the American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Canada, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly American Dietetic Association), approve their use. One of the reasons they are thought to be safe is that most are not metabolized by the body. However, it is possible for nonmetabolized compounds to exert adverse health effects. Recent findings suggest that some high-intensity sweeteners promote dysbiosis, which can in turn increase insulin resistance and blood glucose regulation.

High-intensity sweeteners are used mainly to help people lose weight and gain glycemic control without sacrificing sweet flavors. Unfortunately, the results of several studies suggest that the effects of these substances are counter intuitive; that is, they don't provide the expected benefits and, in some cases, could actually increase weight gain and impair glycemic control. There are several explanations for this. First, studies suggest that when people use sugar-free foods, they make up for the missing calories by eating more food. By eating what's perceived to be a healthy, low-calorie item, people are more likely to give themselves permission to overconsume less-healthful food. The second possible explanation is more about physiology than psychology. When you consume high-intensity sweeteners, your brain thinks you are consuming some thing with calories, but you get less than what your body expects (as happens with calorie-reduced solid foods) or you get none (as with artificially sweetened beverages).

There are two approved high-intensity natural sweeteners. steviol glycosides and luo han guo (monk fruit) extracts. Both are non-nutritive or essentially calorie-free. Steviol glycosides, such as rebaudioside A (also called rebA), stevioside, rebaudioside D, or various mixtures of these compounds, are extracted from the stevia plant. These components are two hundred to four hundred times sweeter than sugar. While these constituents of stevia have been approved for use as sweeteners in the United States, the stevia leaf and crude stevia extracts have only been approved tor use as nutritional supplements and not as sweeteners. Although there is controversy about the safety and side effects of stevia, recent scientific studies have been largely favorable.

Stevia is approved for use in several countries and has been the principal non-nutritive sweetener used in Japan for several decades. Luo han guo, or monk fruit, is a fruit from southern China that has been used in Chinese medicine to treat coughs and sore throats and as a longevity aid. Monk fruit extracts contain a compound called mogrosides, which are 100-250 times sweeter than sugar.

The safety of high-intensity sweeteners is very controversial, although most health organizations, including the American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Canada, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly American Dietetic Association), approve their use. One of the reasons they are thought to be safe is that most are not metabolized by the body. However, it is possible for nonmetabolized compounds to exert adverse health effects. Recent findings suggest that some high-intensity sweeteners promote dysbiosis, which can in turn increase insulin resistance and blood glucose regulation.

High-intensity sweeteners are used mainly to help people lose weight and gain glycemic control without sacrificing sweet flavors. Unfortunately, the results of several studies suggest that the effects of these substances are counter intuitive; that is, they don't provide the expected benefits and, in some cases, could actually increase weight gain and impair glycemic control. There are several explanations for this. First, studies suggest that when people use sugar-free foods, they make up for the missing calories by eating more food. By eating what's perceived to be a healthy, low-calorie item, people are more likely to give themselves permission to overconsume less-healthful food. The second possible explanation is more about physiology than psychology. When you consume high-intensity sweeteners, your brain thinks you are consuming some thing with calories, but you get less than what your body expects (as happens with calorie-reduced solid foods) or you get none (as with artificially sweetened beverages).

This triggers the release or hunger hormones that increase appetite, so again you eat more food. In essence, your ability to regulate the intake of normal foods is decreased when your body expects calories that never come. Another possibility is that the intense sweeteners cause people to become desensitized to sweetness. Sweet whole foods, such as fruits, become less appealing, and you're drawn to less-nutritious foods containing powerful sweeteners; its a slippery slope from a nutritional perspective. Some research suggests that there are sweetness receptors in fat tissue that could trigger weight gain by stimulating the development of new fat cells. Evidence is also building that weight gain may be induced by the negative impact these sweeteners have on the gut microbiome. The bottom line is that sugar alcohols and intense sweeteners are used to enhance the flavor of ultra processed foods and beverages. These are not foods that will help you reclaim your health. Rather, they are the kinds of foods that promote overeating and diabetes. When you stick to whole plant foods, you don't have to worry about intense sweeteners, as they are not found in whole plant foods. It you must use a sweetener during your transition to a whole-foods, plant-based diet, your safest options are derivatives of monk fruit or stevia. Use them in the tiniest amounts possible, with a goal of removing them altogether.

WHAT FIBER CAN DO?

|

Fiber is what gives plants their structure, and its not present in any animal foods. Acting as natures broom, fiber keeps food moving smoothly and efficiently through the intestinal tract. While fiber is a type of carbohydrate, it can't be broken down into digestible sugar molecules like most other carbohydrates. Although it passes through the intestinal tract relatively intact, it has a significant and positive impact. It is well known that fiber prevents constipation, but it can also help lower blood cholesterol and blood pressure, reducing the risk of heart disease. Fiber can improve blood sugar control and insulin sensitivity, reducing the risk of diabetes, and it can diminish the risk of diverticular disease and some cancers, especially colorectal cancer.

|

Fiber also helps to support a healthy gut flora, which supports every body system, including optimal functioning of the brain. People with type 2 diabetes are at increased risk for dysbiosis (unhealthy gut microbiota), which is a key driver of insulin resistance. The most effective way of establishing and maintaining a health-supporting microbiome is to boost the volume and variety of dietary fiber in your diet. For example, to boost volume, add beans to your breakfast. For variety, try brown rice, kamut berries, barley, rye berries, or quinoa. Eat foods rich in probiotics. Consider taking a probiotic supplement that contains several different strains of organisms, and opt for high dosages (at least ten to twenty billion CFUs per day for adults). Check the expiration date.

Also include rich dietary sources of prebiotics to keep Iriendly bacteria well. Minimize very low-fiber and fiber-free foods that foster the growth of bad bacteria. The worst offenders are relined sugars, White flour products, commercial sweeteners, fried foods, meat, and alcohol.

Fiber is commonly divided into two categories. soluble and insoluble. Solubility is determined by whether the fiber dissolves In water. Although these terms are useful the health benefits of fiber are thought to be related more to viscosity (whether fiber becomes gel-like or gummy when mixed with water) and fermentability (whether the fiber can be fermented by gut bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids and gas by-products). Although many soluble fibers are both viscous and fermentable, and insoluble fibers are often nonviscous and nonfermentable, this is not always the case. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will refer to fiber as soluble and insoluble. All fiber-rich foods contain both soluble and insoluble fibers.

Insoluble, nonviscous, less fermentable fiber is more strongly associated with a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Soluble, viscous, fermentable fiber improves postprandial (after meal) blood glucose because it slows the absorption of sugars into the bloodstream. For people who have type 2 diabetes, foods rich in soluble fiber, such as legumes, oats, barley, flaxseeds, and many fruits and vegetables (asparagus, apricots, Brussels sprouts, citrus fruits, parsnips, passion fruit, roots, and tubers, to mention just a few), are especially helpful.

You may have noticed claims about fiber on food labels of processed and refined foods. Some of these products have isolated, non digestible carbohydrates, such as insulin, added to boost the fiber content. While adding fiber to packaged foods boosts fiber and makes them appear healthy, products made with refined flour, sugar, and oil are not good choices-even it they are high in fiber.

The recommended intake for fiber is 14 grams per 1000 calories, or about 29 grams per day tor females and 38 grams per day for males. To kick diabetes, aim to consume at least 45-60 grams of fiber per day (larger individuals can aim for the upper end of the spectrum). This translates to 15-20 grams per meal.

Fiber is commonly divided into two categories. soluble and insoluble. Solubility is determined by whether the fiber dissolves In water. Although these terms are useful the health benefits of fiber are thought to be related more to viscosity (whether fiber becomes gel-like or gummy when mixed with water) and fermentability (whether the fiber can be fermented by gut bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids and gas by-products). Although many soluble fibers are both viscous and fermentable, and insoluble fibers are often nonviscous and nonfermentable, this is not always the case. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will refer to fiber as soluble and insoluble. All fiber-rich foods contain both soluble and insoluble fibers.

Insoluble, nonviscous, less fermentable fiber is more strongly associated with a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Soluble, viscous, fermentable fiber improves postprandial (after meal) blood glucose because it slows the absorption of sugars into the bloodstream. For people who have type 2 diabetes, foods rich in soluble fiber, such as legumes, oats, barley, flaxseeds, and many fruits and vegetables (asparagus, apricots, Brussels sprouts, citrus fruits, parsnips, passion fruit, roots, and tubers, to mention just a few), are especially helpful.

You may have noticed claims about fiber on food labels of processed and refined foods. Some of these products have isolated, non digestible carbohydrates, such as insulin, added to boost the fiber content. While adding fiber to packaged foods boosts fiber and makes them appear healthy, products made with refined flour, sugar, and oil are not good choices-even it they are high in fiber.

The recommended intake for fiber is 14 grams per 1000 calories, or about 29 grams per day tor females and 38 grams per day for males. To kick diabetes, aim to consume at least 45-60 grams of fiber per day (larger individuals can aim for the upper end of the spectrum). This translates to 15-20 grams per meal.

|

Legumes stand out as fiber superstars. Compare foods within each category to see which ones provide the most total and soluble fiber. For example, in the vegetables group, artichokes and Brussels sprouts are very high in both total and soluble fiber. In the legumes group, lentils are extremely high in total fiber, but most other legumes provide more soluble liber.

|

CAN YOU OVER EAT FIBER?

Although it's possible to eat too much fiber, its unlikely if you are consuming whole plant foods and drinking sufficient fluids. Most instances of excessive fiber are generally related to taking fiber supplements, eating too much wheat bran, or not drinking enough. It is surprising to learn that during Paleolithic times, humans consumed an estimated 70-150 grams or more of fiber per day. This is more than the highest fiber levels eaten today

Although it's possible to eat too much fiber, its unlikely if you are consuming whole plant foods and drinking sufficient fluids. Most instances of excessive fiber are generally related to taking fiber supplements, eating too much wheat bran, or not drinking enough. It is surprising to learn that during Paleolithic times, humans consumed an estimated 70-150 grams or more of fiber per day. This is more than the highest fiber levels eaten today

For some individuals, however, a sudden increase in fiber intake may cause abdominal discomfort, cramping, bloating, gas, and diarrhea. It is even possible to become constipated when consuming a lot of fiber without enough fluids. In the most severe cases, it's possible to develop an intestinal blockage. This can happen if the fiber becomes a hard, dry mass in the intestine, blocking the passage of food. The best way to prevent the adverse effects of a high-fiber diet is to increase your intake gradually (over several weeks) and boost your fluid intake along with it.

Another concern is that very high fiber intakes can reduce the absorption of minerals. While research has shown a reduction in the absorption of some minerals, the impact tends to be fairly small. Also, it's not clear if fiber itself is the culprit or if phytates and oxalates, which can bind to minerals, bear more of the responsibility. Although this is a valid concern, these minerals can be liberated, at least partly, during fermentation in the large intestine. Short-chain fatty acids (also products of fermentation) help to facilitate their absorption from the large intestine. In addition, when compared to refined foods, high-fiber whole foods generally provide enough extra minerals to compensate for any losses incurred. Regardless, it is advised to limit concentrated fiber, such as wheat bran, and to minimize the use of fiber supplements when eating a plant-based diet. The best balance of healthful fiber and nutrients comes naturally with a varied whole-foods, plant-based diet.

The Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load

The glycemic index (GI) is a measure of how carbohydrates impact blood sugar levels. Carbohydrates with a high GI are more quickly digested, absorbed, and metabolized, causing a rapid and dramatic rise in blood glucose. Foods with a high GI

usually trigger an exaggerated insulin response, adversely affecting long-term blood glucose control, increasing triglycerides, and reducing protective HDL cholesterol. Carbohydrates with a low GI are more slowly digested, absorbed, and metabolized, causing a lower and more gradual rise in blood glucose. Foods with a low GI may positively affect insulin response, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol levels. Replacing high GI foods with low GI foods improves blood sugar control, reduces a hsCRP (a measure of inflammation), and significantly reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

To determine the glycemic index of a food, several people eat a sample of the food providing 50 grams of carbohydrate. For each study participant, changes in blood glucose are monitored over time (usually two hours). The values from all of the participants are averaged to obtain the glycemic index of the food. The GI uses a scale of 0 to 100, with higher values given to foods that cause the most rapid rise in blood sugar. Pure glucose serves as a reference point and is given a Gl of 100. White bread has a glycemic index of 75 relative to glucose, which means that the blood sugar response to the carbohydrate in white bread is 75 percent of the blood sugar response to the pure glucose. By comparison, barley has a glycemic index of 28 relative to glucose. The glycemic index tells us how a serving of food containing 50 grams of carbohydrates affects our blood sugar. However, we rarely consume exactly 50 grams of carbohydrate from any food. Therefore a more practical tool called the glycemic load (GL) was created so the glycemic impact of a food could be estimated based on the carbohydrate in a typical serving size (based on the USDA food database). GL is calculated by muliplying the glycemic index by the grams of carbohydrate provided in a portion of the food and dividing the total by 100. The formula for calculating GL is as follows:

usually trigger an exaggerated insulin response, adversely affecting long-term blood glucose control, increasing triglycerides, and reducing protective HDL cholesterol. Carbohydrates with a low GI are more slowly digested, absorbed, and metabolized, causing a lower and more gradual rise in blood glucose. Foods with a low GI may positively affect insulin response, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol levels. Replacing high GI foods with low GI foods improves blood sugar control, reduces a hsCRP (a measure of inflammation), and significantly reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

To determine the glycemic index of a food, several people eat a sample of the food providing 50 grams of carbohydrate. For each study participant, changes in blood glucose are monitored over time (usually two hours). The values from all of the participants are averaged to obtain the glycemic index of the food. The GI uses a scale of 0 to 100, with higher values given to foods that cause the most rapid rise in blood sugar. Pure glucose serves as a reference point and is given a Gl of 100. White bread has a glycemic index of 75 relative to glucose, which means that the blood sugar response to the carbohydrate in white bread is 75 percent of the blood sugar response to the pure glucose. By comparison, barley has a glycemic index of 28 relative to glucose. The glycemic index tells us how a serving of food containing 50 grams of carbohydrates affects our blood sugar. However, we rarely consume exactly 50 grams of carbohydrate from any food. Therefore a more practical tool called the glycemic load (GL) was created so the glycemic impact of a food could be estimated based on the carbohydrate in a typical serving size (based on the USDA food database). GL is calculated by muliplying the glycemic index by the grams of carbohydrate provided in a portion of the food and dividing the total by 100. The formula for calculating GL is as follows:

Glycemic Load (GL) = Gl x CHO content per portion of food divided by 100.

So, for example, the GL of brown rice with a GI of 66 and 52 grams of carbohydrate per a 1-cup (250-ml) serving would be: 66 x 52 100 = 34.

The critical point about GL is that serving size matters. For example, it you ate 2 cup (125 ml) of the brown rice (GI = 66; 26 g carbohydrate), the GL would be 17 (66 x 26/100). If you ate 2 cups (500 ml) of brown rice (GI = 66; 104 g carbohydrate), the GL would be 68 (66 x 104/100)! Both the GI and GL are rated as being low, medium, or high according to their impact on blood glucose.

A GI of 55 or less is low, 56-69 is medium, and 70 or more is high. A GL of 10 or less is low 11-19 is medium, and 20 or more is high. Foods that have a high glycemic index do not always have a high glycemic load. For example, watermelon has a glycemic index of 72; however, a 4-ounce (120-g) serving of watermelon provides only 6 grams of carbohydrate. You would need to eat over eight servings (2 lbs/960g) of watermelon to get the 50 grams of carbohydrates needed to determine its glycemic index. A 4-0unce (120-g) serving of watermelon has a glycemic load of 4 (72 x 6 /100), which is low.

So, for example, the GL of brown rice with a GI of 66 and 52 grams of carbohydrate per a 1-cup (250-ml) serving would be: 66 x 52 100 = 34.

The critical point about GL is that serving size matters. For example, it you ate 2 cup (125 ml) of the brown rice (GI = 66; 26 g carbohydrate), the GL would be 17 (66 x 26/100). If you ate 2 cups (500 ml) of brown rice (GI = 66; 104 g carbohydrate), the GL would be 68 (66 x 104/100)! Both the GI and GL are rated as being low, medium, or high according to their impact on blood glucose.

A GI of 55 or less is low, 56-69 is medium, and 70 or more is high. A GL of 10 or less is low 11-19 is medium, and 20 or more is high. Foods that have a high glycemic index do not always have a high glycemic load. For example, watermelon has a glycemic index of 72; however, a 4-ounce (120-g) serving of watermelon provides only 6 grams of carbohydrate. You would need to eat over eight servings (2 lbs/960g) of watermelon to get the 50 grams of carbohydrates needed to determine its glycemic index. A 4-0unce (120-g) serving of watermelon has a glycemic load of 4 (72 x 6 /100), which is low.

The impact of decreasing the GL of the diet is measurable and proportionate. One study reported that the risk of developing diabetes is increased by 45 percent for every 100-gram increment of GL. (To get the total GL for the day, add up the GL of each food consumed). To put this into perspective, 100 grams of GL is equal to 100 grams of carbohydrate from food with a GI of 100, 200 grams of carbohydrate from food with a GI of 50, and 300 grams of carbohydrate from food with a GI of 33. The lesson here is that the glycemic impact from a small serving of blood with a high GI can be remarkably similar to a much more generous serving of a food with a low GI.

The GI of various foods is not as predictable as one might expect. For example, sucrose (white table sugar) has a glycemic index of 68 - lower than that of white bread which has a glycemic index of 75, or whole wheat bread, which has a glycemic index of 74. How can't be that bread, a complex carbohydrate, has a glycemic index that is higher than table sugar, a simple carbohydrate? The reason is that table sugar is half fructose and half glucose, while bread is all glucose. Glucose goes directly into the bloodstream and has the greatest impact on blood sugar. Fructose is metabolized quite differently, and its impact on blood sugar is about one-fifth that of glucose. So while bread may be more slowly digested and absorbed than sucrose, the glucose in bread causes a greater rise in blood glucose than the combination of glucose and fructose present in table sugar. There are several key factors influencing the glycemic index of foods.

TYPE OF SUGAR PRESENT

Glucose has a much greater impact on blood glucose than fructose or galactose (a sugar in milk). When comparing the glycemic index of various types of natural sweeteners, the differences are determined by the relative amount of fructose contained in the sugars. Sugars with a lower GI contain more fructose. This does not make them more healthful. Although sugar alcohols aren't technically sugars, their GI ranges from zero for erythritol to 36 for maltitol; other sugar alcohols have a GI of 5-12.

TYPE OF STARCH PRESENT

The two principal starches in foods amylopectin and amylose are digested at very different rates. Amylopectin is a highly branched chain of glucose molecules that are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. Amylose, a more compact, straight chain of glucose molecules is broken down relatively slowly. Foods that are higher in amylose have lower GIs. It you look at very detailed GI charts, you will notice that the GI of different types of rice varies wildly, with those low in amylose and high in amylopectin having a much higher GI.

AMOUNT AND TYPE OF FIBER PRESENT

Fiber resists the work of digestive enzymes, so to slows the digestion and absorption of sugars from foods, reducing GI. Foods rich in soluble, viscous fiber reduce the glycemic index to a greater extent than foods rich in insoluble. Nonviscous fiber. Beans and barley are good examples of foods rich in viscous fiber wheat bran is a good example of a food rich in nonviscous fiber. Refined foods that have had most or all of their fiber removed have a higher GI, as they are more rapidly absorbed.

The GI of various foods is not as predictable as one might expect. For example, sucrose (white table sugar) has a glycemic index of 68 - lower than that of white bread which has a glycemic index of 75, or whole wheat bread, which has a glycemic index of 74. How can't be that bread, a complex carbohydrate, has a glycemic index that is higher than table sugar, a simple carbohydrate? The reason is that table sugar is half fructose and half glucose, while bread is all glucose. Glucose goes directly into the bloodstream and has the greatest impact on blood sugar. Fructose is metabolized quite differently, and its impact on blood sugar is about one-fifth that of glucose. So while bread may be more slowly digested and absorbed than sucrose, the glucose in bread causes a greater rise in blood glucose than the combination of glucose and fructose present in table sugar. There are several key factors influencing the glycemic index of foods.

TYPE OF SUGAR PRESENT

Glucose has a much greater impact on blood glucose than fructose or galactose (a sugar in milk). When comparing the glycemic index of various types of natural sweeteners, the differences are determined by the relative amount of fructose contained in the sugars. Sugars with a lower GI contain more fructose. This does not make them more healthful. Although sugar alcohols aren't technically sugars, their GI ranges from zero for erythritol to 36 for maltitol; other sugar alcohols have a GI of 5-12.

TYPE OF STARCH PRESENT

The two principal starches in foods amylopectin and amylose are digested at very different rates. Amylopectin is a highly branched chain of glucose molecules that are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. Amylose, a more compact, straight chain of glucose molecules is broken down relatively slowly. Foods that are higher in amylose have lower GIs. It you look at very detailed GI charts, you will notice that the GI of different types of rice varies wildly, with those low in amylose and high in amylopectin having a much higher GI.

AMOUNT AND TYPE OF FIBER PRESENT

Fiber resists the work of digestive enzymes, so to slows the digestion and absorption of sugars from foods, reducing GI. Foods rich in soluble, viscous fiber reduce the glycemic index to a greater extent than foods rich in insoluble. Nonviscous fiber. Beans and barley are good examples of foods rich in viscous fiber wheat bran is a good example of a food rich in nonviscous fiber. Refined foods that have had most or all of their fiber removed have a higher GI, as they are more rapidly absorbed.

PHYSICAL BARRIER AROUND THE FOOD

Beans and whole grains are surrounded by a fibrous coating that serves as a physical barrier to protect the seed. This barrier makes it more difficult for enzymes to break the food down, reducing the GI.

RIPENESS OF THE FOOD

As foods ripen, starches turn into sugars that are more rapidly digested, increasing their GI. For example, a banana that is slightly green or under ripe has a GI of about 50, while an overripe banana has a GI of about 50.

EXPOSURE TO HEAT

Raw foods have a lower GI than the same foods cooked. Cooking increases GI because it breaks down the plant's cell walls, increasing the rate at which its starches and sugars are absorbed. Lightly steaming vegetables to the tender-crisp stage will result in a lower GI than very well-cooked vegetables.

PARTICLE SIZE

Whenever particle size is reduced, the surface area of the food is increased, and it is more rapidly digested and absorbed. Thus, intact whole grains (such as wheat berries and barley) have a much lower GI than ground grains (flours), and whole fruits have a lower GI than fruit sauces or juices.

DENSITY OF THE FOOD

Dense foods containing little air have a lower GI than foods that are light and fluffy Even though white flour is the main ingredient in white bread and white pasta, the bread has a much higher GI than the pasta because it is light and fluffy and quickly broken down. Puffed cereal grains also have a much higher GI than cooked grains.

CRYSTALLINITY OF THE FOOD

When a starch is raw, it is crystalline, its molecules are organized in a sequence that repeats. When it is cooked, this order is lost; it becomes more easily broken down and digested, and the GI increases. However, when the food cools, it recrystallizes, reducing its GI. For example, red potatoes cubed and boiled in their skin have a GI of 89. When the potatoes are stored overnight in the refrigerator and eaten cold the next day, the GI drops to 56.

ACIDITY

The addition of vinegar, lemon, or lime, ideally near the beginning of your meal perhaps on a salad, can reduce the glycemic impact of the meal. Even 2-3 teaspoons (10-15 ml) is often enough for an effect. Fermentation also produces acid, reducing the GI. Yogurt has a lower GI than fluid milk, and sourdough bread has a lower GI than conventional bread.

Beans and whole grains are surrounded by a fibrous coating that serves as a physical barrier to protect the seed. This barrier makes it more difficult for enzymes to break the food down, reducing the GI.

RIPENESS OF THE FOOD

As foods ripen, starches turn into sugars that are more rapidly digested, increasing their GI. For example, a banana that is slightly green or under ripe has a GI of about 50, while an overripe banana has a GI of about 50.

EXPOSURE TO HEAT

Raw foods have a lower GI than the same foods cooked. Cooking increases GI because it breaks down the plant's cell walls, increasing the rate at which its starches and sugars are absorbed. Lightly steaming vegetables to the tender-crisp stage will result in a lower GI than very well-cooked vegetables.

PARTICLE SIZE

Whenever particle size is reduced, the surface area of the food is increased, and it is more rapidly digested and absorbed. Thus, intact whole grains (such as wheat berries and barley) have a much lower GI than ground grains (flours), and whole fruits have a lower GI than fruit sauces or juices.

DENSITY OF THE FOOD

Dense foods containing little air have a lower GI than foods that are light and fluffy Even though white flour is the main ingredient in white bread and white pasta, the bread has a much higher GI than the pasta because it is light and fluffy and quickly broken down. Puffed cereal grains also have a much higher GI than cooked grains.

CRYSTALLINITY OF THE FOOD

When a starch is raw, it is crystalline, its molecules are organized in a sequence that repeats. When it is cooked, this order is lost; it becomes more easily broken down and digested, and the GI increases. However, when the food cools, it recrystallizes, reducing its GI. For example, red potatoes cubed and boiled in their skin have a GI of 89. When the potatoes are stored overnight in the refrigerator and eaten cold the next day, the GI drops to 56.

ACIDITY

The addition of vinegar, lemon, or lime, ideally near the beginning of your meal perhaps on a salad, can reduce the glycemic impact of the meal. Even 2-3 teaspoons (10-15 ml) is often enough for an effect. Fermentation also produces acid, reducing the GI. Yogurt has a lower GI than fluid milk, and sourdough bread has a lower GI than conventional bread.